At a tennis center on Chicago’s southside, my sister and I wait for my nephew’s game to start. Courts of teenage boys face each other in singles and doubles matches. The whack of tennis balls hitting racquets echoes through the space. It smells of sweat and dirty socks.

My sister has found me a chair, so I don’t have to put weight on my broken foot. When she invited me, she was clear: “You need to get out of your apartment, even if just for a little bit.”

It’s not going well—all the healing I’m trying to do. I keep walking on my broken foot. And then there’s the whole recovering-from-twenty-five-years-of-serious-mental-illness thing.

My new psychiatrist, Dr. R, recently spoke to me about recovery. In all the years I was in the mental health system, not one clinician mention getting well; the best I could do was “manage” my symptoms. My diagnosis was biological and lifelong—inside me, never to be resolved.

Which would have been fine if it were true. Turns out no psychiatric diagnosis is purely biological or necessarily a life sentence.

Three-quarters into the qualifying match, my nephew’s losing. The other player is good. If his first serve hits the net or goes out, he lobs his second, which throws off my nephew’s rhythm.

This tournament will affect my nephew’s ranking and determine whether he qualifies for the state championship at the end of the season.

My nephew is best described as solid—emotionally, physically, mentally. He loses, is disappointed, and gets over it. Within hours, he’s cracking jokes and smiling. Not that things don’t get to him; they just don’t absorb him.

It’s pretty clear he’s going to lose. He uses his shirt collar to wipe the sweat from his forehead and under his glasses and mutters in frustration.

Then he regains focus.

Everything comes together: his serve, his backhand, his agility. He plays loose and light as if he’s never had a moment’s frustration or doubt the whole game.

During match point (in my nephew’s favor), they volley for what seems like a very long time.

Then: he wins. I want to leap to my feet with joy but can’t.

Before leaving the arena, my sister and I stop to talk to his coach—an older, chubby, balding man. He gushes with enthusiasm over my nephew’s win. “Amazing. He crushed it.” The coach holds up his phone. “This is what we listened to in the van on the way down here. And it did it.”

Onscreen is a YouTube video—black and white—of a guy wearing headphones speaking into a mic. His head is shaved. His face is acutely square, his jaw severe. He has the neck of a serious weightlifter.

My nephew’s coach says, “Jocko Willink. He’s why your nephew won today.”

I get home, google, and learn that “Jocko,” as he’s known, is a phenom. A retired Navy Seal who served in Iraq, he’s published books on leadership and runs a company that serves as a pseudo-military training ground for businessmen who want to lead as if they’ve once been Navy Seals even though haven’t. Jocko’s passion is Jiu-Jitsu. His YouTube motivational speeches and interviews get millions of views. His podcast has tens of millions of downloads.

If he helped my nephew, maybe Jocko can help me.

Within a week, I’m deep into the world of Jocko. I dip in at first, catching clips of his motivational speeches on YouTube. Soon,

I’m listening to the full one-to-two-hour podcasts.

My fascination morphs into infatuation and then fixation.

Most of his guests are soldiers or leaders who’ve experienced hardships I couldn’t begin to fathom. Jocko’s three-hour interview with Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Ron Shurer, a staff sergeant who served as a medic in Afghanistan and then in the secret service and was also battling cancer, holds me rapt.

On another episode, Jocko interviews a vet who’s a quadruple amputee who runs a center for other quadruple amputees and their families.

Another interview is with a vet who’s a double amputee and runs multiple marathons each year to raise money for a nonprofit.

When Jocko addresses us, his devoted listeners, he’s all grit. He says life is war. We need discipline and to take responsibility for our actions. In his gravelly voice, he tells us to “crush it”—“it” being any project or task. He urges us to “get after it.”

We have to be ultra-aggressive, ultra-confident, and uber-in-control.

Jocko is problematic in many ways. He refers to women as “girls,” talks way too much about Jiu-Jitsu, and often comes off as melodramatic. At the end of his show, he sells Jocko-sponsored-and-made merchandise like T-shirts and krill-oil supplements and (for reasons I can’t begin to grasp) soap.

It’s bro-culture in the extreme, but in a way, it works. Telling myself to attack, push, pursue gives me the courage to stop obsessing over my broken foot, my broken brain, my brokenness.

When one of his listeners emails to say that he’s considering suicide, Jocko says that suicide is never an option because when you’re on your last bullet, you shoot the enemy, not yourself—the enemy being something along the lines of whatever difficulties you’re facing.

Sitting in my apartment with my broken foot elevated, unable to walk (my long, long walks were the one thing helping me in my mental health recovery), he becomes an abrasive balm.

He seems to have what I want: the power to heal.

*

According to mental health professionals and patient advocacy groups, Jocko’s toughen-up approach is ill-advised when it comes to mental health recovery.

The patient advocacy group Mental Health America (MHA) warns that “tough love” can backfire. Pushing through is the equivalent of walking in the boot, putting weight on a broken bone.

Self-love, self-compassion, and vulnerability are the preferred methods of mental health care.

I learned a lot about this triad in my first partial hospitalization program (PHP). In the PHP, we’d sit in a circle in a frigidly air-conditioned therapy room and learn “skills” to deal with our respective issues or mental illnesses.

The staff recommended books by self-help gurus, psychologists, and researchers.

The favorites—and I mean favorites—were self-compassion icon Dr. Kristin Neff and vulnerability guru Brené Brown.

Neff defines self-compassion as “being warm and understanding toward ourselves.” Self-love has lots and lots of definitions, most of which have to do with “an appreciation of one’s own worth.”

Brown’s version of vulnerability entails embracing uncertainty, allowing weakness, and revealing our inner thoughts and emotions to others.

But herein lies the crux of the vulnerability paradox: It says that those who visibly embrace their weaknesses are strong whereas those who don’t are weak because we don’t expose our weaknesses.

And it seemed easy for Neff and Brown, two privileged women who’d never experienced a mental health crisis (let alone too many to count), to tell us to embrace what American culture deems weakness and make ourselves vulnerable.

As far as I was concerned, I’d been weak and vulnerable enough.

*

My nephew’s tennis season continues and he’s on a winning streak. I get texts from my sister telling me how he’s won this match and that match.

When a black wave of depression comes over me, I harden against it. No, I say. Not happening.

When anxiety seizes me, sending sweaty, sickening rushes of panic through my body, I do the same. No. Not happening.

Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t. But I say it every time until it works more often. When darkness envelopes me, I don’t stop to show myself compassion. I don’t “turn towards it.” When I feel afraid, I don’t “lean into it;” I steel myself and move on.

Healing is in my control. I’m going to do it despite the hum in my chest and surges of energy and the dark pit in my stomach and my pounding heart and my numb lips and cheeks and the sense that I’m not really there.

*

I’m in my apartment grading essays when a text comes in from my sister. It’s a photo of my nephew. He’s outside, a tennis court in the background. His green T-shirt is soaked with sweat. In his hands is a trophy. He’s won the conference title.

I don’t know what he thought or said to himself to win all those games. All I know is that every day, he was on the court, playing.

I hobble to the kitchen and fill my espresso maker with water and coffee grounds, seal it, and turn on the stove. My ankle aches. Teaching the day before, I stood too long at the podium, wanting to give the presentation standing up, the way I would have before I broke my ankle.

Later, I’ll realize that I was already tough—long before Jocko; I’d just lost sight of it.

People with mental illness are some of the strongest people on earth.

You have to be fierce to be in that struggle—regardless of whether one heals.

*

Around the room are weights, massage tables, a stationary bike, a treadmill, and yoga mats. Resistance bands hang from the wall. In the corner sits an enormous, inflated exercise ball.

Colleen, the physical therapist I’ve been assigned is very nice and very pregnant. She’s also very fit. She’s a runner and still runs long distances in her eighth month.

It’s my third time seeing her. I take off the boot and lie on the massage table on my back. I had visions of physical therapy being restful and relaxing, but it’s tedious and painful. Colleen is more taskmaster than therapist.

She stands next to the table and commands me to point my toes fifteen times. Restoring range of motion is the first step of physical therapy for a broken foot. Next will come strength and balance.

“Flex—then rotate left and then right,” she says.

Dr. Patel said I could be out of the boot as soon as my next appointment, so I do as I’m told.

An elderly man lies on the massage table next to mine. Liver spots dot his balding head and hands. A physical therapist moves his body, which is so thin it looks as if his bones might break.

Pain shoots through my ankle as I let my toes return to neutral. I wince.

“You don’t have to push so hard,” Colleen says.

The physical therapist gently rotates the man’s arm. The man’s face is passive, accepting.

When I’m finished, Colleen hands me the exercise band and tells me to do the same exercises using it as resistance. With her arm resting on her belly, she walks away.

I loop the band under my foot and, holding it, point my toes and return to neutral. Point and return. Point and return. My ankle is stronger. It has to be.

Colleen comes over and asks how I’m doing. She doesn’t know how important healing is right now.

I tighten my grip on the band, rotate my ankle left, and return to neutral. “I can do another set.”

Her brow furrows. “You don’t have to.”

*

Dr. Patel gently places his fingers on my still intensely bruised ankle. Behind him is a medical resident. The resident looks at the x-ray of my ankle with a skeptical look on his face, as if to say, I wonder how that’s going to heal.

“It doesn’t hurt,” I say for the second time during the visit, even though it isn’t true.

He and the resident exchange glances.

I want to heal. “It feels better.”

With a sigh, he turns to the computer monitor and starts typing. “Do you know what happens when you break a bone?” He clicks the keys. “The bone bleeds. Your bones contain blood vessels, and when the bone breaks, they clot and pool around the broken ends. That clotted blood has to become solid bone.”

The gravity of what he’s saying, the tone of just slow down, let yourself heal doesn’t register. “How close are we to being out of the boot?”

He continues typing, eyes on the monitor. “We’re only in phase two.”

I ask how many phases there are.

“Three, basically. You’ve been through the inflammatory phase, fracture hematoma formation. The blood clots have done their job. Your ankle is now in the repaired phase.”

I like that it’s called the repaired stage, not repairing or potentially repairing. It’s repaired. Healing is inevitable—a done deal—so unlike the way the many mental health clinicians I saw spoke of the psychiatric diagnoses they gave me over twenty-five years.

He points to the X-ray on the computer monitor. The resident looks over his shoulder.

I ask if I can get the short boot, the quaint one that looks more like a shoe than a Storm Trooper boot.

They turn to me, their expressions an almost audible no. “This is the deep healing phase. Fibrous tissue and cartilage have to form a soft callus at the ends of the broken bone. They’ll join, and the hard bone will replace the soft tissue. This is serious.”

“And then we’re done?” What they don’t understand is that I’m also trying to heal from mental illness. My new psychiatrist has said it’s possible—even for me, whom other doctors had condemned to lifelong suffering—and although I doubted him at first, I want it desperately. It’s taking too long too.

“We’ll see,” he says, standing. “Stay in that boot.”

*

Clifford Beers has become one of my heroes—in a way.

Beers’s memoir A Mind that Found Itself is a harrowing account of his breakdown in 1900, his suicide attempt (he jumped from a second-story window, feet first), and hospitalizations in one asylum after another.

The conditions Beers met with in the asylums made him worse. He was put in straitjackets, physically abused, emotionally berated, and isolated in a padded cell, among other injustices. While at the Connecticut State Hospital at Middletown, he vowed to get well and write a memoir campaigning for reform so no other patient would experience the horror he did.

His descent into hypochondria and depression and panic and paranoia and finally mutism make my experiences of mental illness pale in comparison.

A Mind that Found Itself doesn’t tell only of madness, as so many mental-illness memoirs do; it describes how he healed:

“I have already described the peculiar sensation which assailed me when, in June, 1900, I lost my reason. At that time my brain felt as though pricked by a million needles at white heat. On this August 30th, 1902, shortly after largely regaining my reason, I had another most distinct sensation in the brain. It started under my brow and gradually spread until the entire surface was affected. The throes of a dying Reason had been torture. The sensations felt as my dead Reason was reborn were delightful. It seemed as though the refreshing breath of some kind Goddess of Wisdom were being gently blown against the surface of my brain. It was a sensation not unlike that produced by a menthol pencil rubbed ever so gently over a fevered brow. So delicate, so crisp and exhilarating was it that words fail me in my attempt to describe it. Few, if any, experiences can be more delightful.”

I know that sensation in the brain now. I can’t relate to “a menthol pencil rubbed ever so gently over a fevered brow,” but I’ve felt the delicacy, crispness, exhilaration, and delight of becoming well—fully well.

For twenty-eight years, Beers worked tirelessly to eradicate the inhumane treatment patients suffered and improve attitudes toward those with mental illness.

He joined forces with the eminent psychiatrist Adolph Meyer and the philosopher William James. Together, they founded the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, which researched the causes of mental disorders, trained medical students, and helped pass legal reforms on behalf of patients. The mental hygiene movement sought to move away from strictly biological explanations of mental illness and examine the patient’s history, community, and environment as potential causes and cures. The National Committee for Mental Hygiene later became the patient advocacy group Mental Health America (MHA).

The mental hygiene movement had a serious dark side. It later focused on eugenics. Citing the supposed permanence and heritability of mental illness, the movement sought to prevent people with mental illness from procreating by sterilizing them. This, too, lent to the mistaken idea that mental illness is hopeless and lifelong.

Beers’s life didn’t end happily. In 1939, he succumbed to depression and nervous exhaustion. He eventually committed himself to Providence, Rhode Island’s Butler Hospital, a psychiatric institution, where he died four years later.

Maybe he didn’t fully recover, but I will, and I’ll help change the mental health system.

*

Dr. Patel stands smiling before me, flanked by a resident—this one as boyishly young as the others. The office seems larger than it did before, less medical, more pleasant.

We’re in phase three: the remodeled phase. Solid bone will continue to grow, and blood circulation around where the break occurred will eventually improve.

He turns to the computer monitor and clicks the mouse. Onscreen is the x-ray of my ankle. The bones don’t look as if they’ve joined correctly. Dr. Patel explains that they’re supposed to be uneven.

“How long will it take to heal completely?” I hop off the examination table.

“It depends. It can take six months or longer.”

“How much longer?”

“To be fully cured, it can take years.” He types something. The words logging out appear onscreen. “It’s a slow process. It’s actually the majority of the healing time.”

“How many years?”

“You won’t need to come back in, but you’ll continue physical therapy.” The screen goes dark. “Gradual weight-bearing exercises are encouraged.”

I stride down the hallway on my out, carrying the boot. It’s a sunny early-summer day, not too hot. In the first trash can I see, I toss the boot.

Along the lakefront path, I walk and walk. There’s pain, but I ignore it. The fresh air seems fresher, the lake bluer, the sky brighter.

By the time I get back to my apartment, I’m limping. The room is dark. Out the window, my sliver of sky is starting to cloud over.

*

“You shouldn’t have done that,” Colleen says at our next appointment.

Holding onto the exercise band looped around my foot, I point my toes.

“Now rotate right,” Colleen says. “You have to think long-term and not push it.”

She wouldn’t understand that I think only about living as someone already healed.

“You aren’t out of the woods yet,” she says, echoing Dr. Patel. “The remodeled phase takes time.”

I rotate my ankle once, twice, counting, taking my time to reach fifteen.

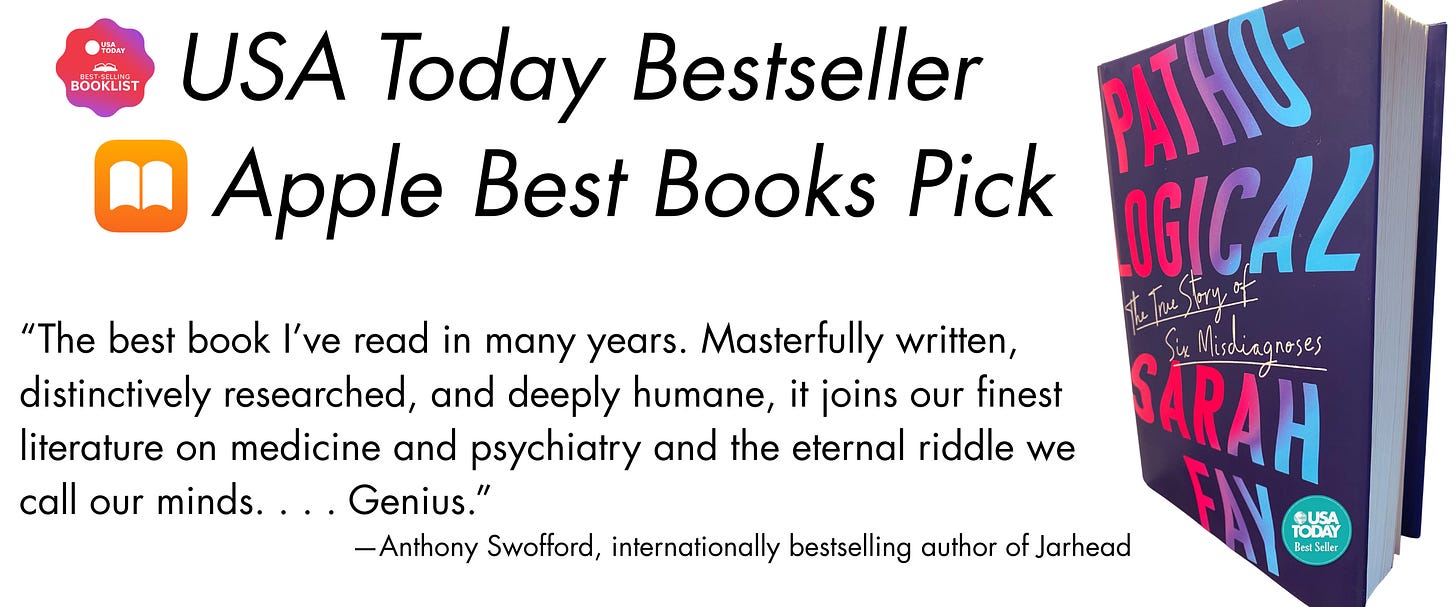

Thank you for reading! You can buy my national bestselling memoir Pathological, hailed by The New York Times as “a fiery manifesto of a memoir.”

Pathological traces how we’ve come to believe that ordinary emotions are mental disorders.

If you’ve already purchased a copy, thank you! You can gift a copy to a friend, your local library, or your favorite used bookstore.

I’ve struggled with depression and anxiety my whole life, exacerbated by an emotionally abusive marriage, then three years of court battles with my ex over our daughter (I’m writing a memoir about all that). I wouldn’t call it severe or debilitating, but it’s bad enough. Just recently I started to implement a more “Jocko” approach (incidentally, I went to elementary and Junior High with him!) by telling myself “You are strong, you can get through this.” Which has helped pretty well with not going into shutdown/collapse. I think both the tough love and the self compassion are needed at different points. It’s a balance I’m always feeling around to find.

Thanks for this thought provoking essay!

Sometimes our mental toughness overpowers our physical capabilities! I enjoyed this and will check out Jocko Willink's podcast!