My idea about what it meant to recover from serious mental illness got tangled up with the American obsession with being very, very social.

Having friends can be wholesome and fortifying, but not when it’s seen as evidence that we’re worthy. The misconception is that if we have lots and lots of people around, then we’re okay. This line of thinking leads us to regularly attend brunch when we don’t want to, tally the number of people who wish us a happy birthday, take likes and shares on social media seriously, and believe we should have fifty friends instead of the more reasonable (and more common) two or three.

The term introvert is thrown around too easily and defined in different ways, but in the sense that some people are fueled by being alone and enjoying their own company, I suppose it applies to me.

I’ve always been a solitary, albeit a sociable one. I don’t hunger to be around others. Small talk with my neighbors, being with my family, and cat videos on Instagram meet a surprising amount of my need for connection.

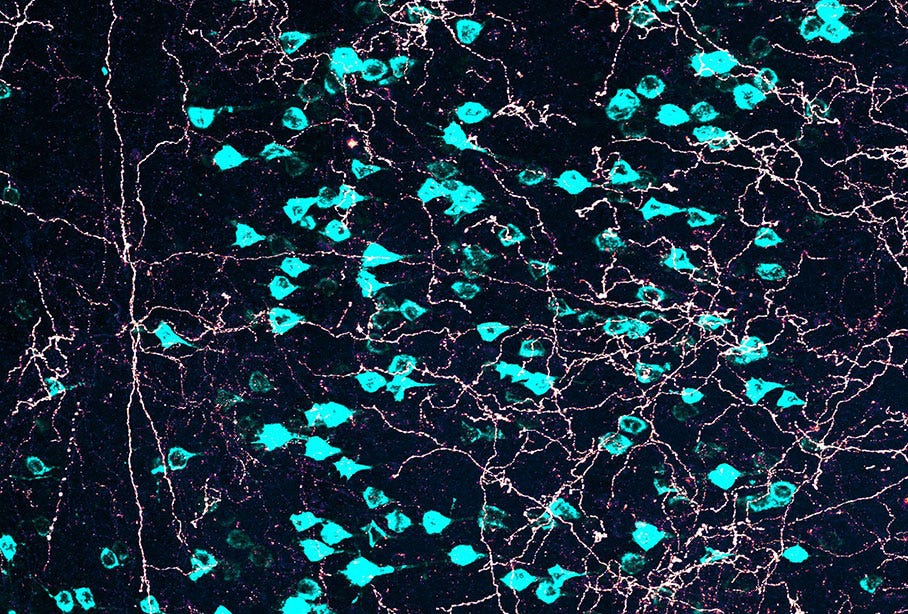

Some of us are hardwired for solitude. Researchers theorize that our brains have a social circuitry that strives for homeostasis. When it’s depleted, some people need a lot of interaction to get even a faint dopamine hit; others need little interaction to get the same bump.

Much is made about how important social connection is to our mental well-being, and social support is considered fundamental to mental health recovery. One’s social support network includes someone to do things with, someone who can give emotional support, someone who can validate you and what you might be going through, someone who can do you a favor like driving you to a medical appointment, and someone who has the knowledge to guide you through a problem or help you reach a goal.

But the data is fuzzy when it comes to how much being social helps one heal from mental illness.

Ultimately, in any study on social connection and mental health, there’s no way to tell if socializing spurs recovery or if those who’ve recovered have more social interactions.

Still, I decided that people—“well” people—are social. They go to brunch and parties and don’t feel at all miserable.

I started by going with my family to the theater. To my mother, who’d been my caregiver, almost any musical theater production is a must-see. She raised us on musicals, taking us to see them and playing recordings of Oklahoma! and My Fair Lady and Cats. I knew all the words to “When I Take You Out in My Surry” before I could say the Pledge of Allegiance. My mother saw her share of heady, intellectual theater too, but she preferred “a little song and a little dance,” as she put it, and a happy ending.

But halfway through A Chorus Line, the small theater felt like it was swallowing me. Something is wrong. I have to get out of here. I’m breaking. During the finale, my heart pounded practically in time with each leg lift in the kick line.

I forced myself to go again. At a local production of “Jesus Christ Superstar,” I sat alongside my nephew, niece, sister, brother-in-law, and mother and watched the show. Onstage, the lead actor was in a makeshift jail. He wore only a loincloth and sang of his woes. His voice was redolent, steady, Broadway quality. The rest of the production was less Broadway and more community theater.

I was there but also detached—what psychiatry calls derealization and depersonalization. My thoughts raced about how long the play would last, how long it would take us to get home, etc., etc.

The lead actor with the Broadway voice sang a refrain from an earlier song. The curtain call went on and on. My hands hurt from clapping. I managed to get through standing ovation after standing ovation without breaking down.

While trying to recover, I saw so many plays and musicals. During each one, I had a panic attack or felt like I was disappearing or that the people around me weren’t real.

But it started to happen less and less.

But I never became social—in the traditional sense. Never the well-adjusted woman with lots of friends, following them on social media, a “tribe” with whom to celebrate “Galentine’s Day.”

I’ve been recovered for five years, and I’m nothing like the well-adjusted woman. In fact, my life looks surprisingly similar to how it did when I was sick. It’s quiet. I love to stay home with my cats. Years ago, in writing about the differences between solitude and isolation for Longreads, I described solitude as “a strength…a skill to be mastered.”

A psychiatrist might diagnose me with social anxiety disorder. The difference is that these are all choices I’ve made, ones that further my goals and give me the life I want.

*

Full recovery from mental illness took understanding how my brain works, learning to experience my thoughts, allowing my emotions, and directing my behaviors toward the pursuit of goals. Psychiatric diagnoses supposedly demarcate where our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors become pathological, meaning abnormal and/or a problem.

But what is a thought? Philosophers have a lot to say about thoughts and thinking, but it’s not practical. If we side with the physicalists and believe that the mind is a series of neurophysiological reactions produced by our brains, then thoughts are representations of the real world as discerned by various parts of the brain as communicated by our neurons. Thoughts represent that which we sense (a person’s finger on our upper lip), feel (humiliation), or plan (leave and not look back or stay and convince ourselves it’s fine, really).

For someone whose thoughts seem to be out of control—typically racing and running contrary to each other and to reality—the mind can be a terrible place. It’s ragged and harrowing. Relentless. Fragments of thoughts spin out, colliding into other thought fragments, making us feel cracked and splintering. Other times, thoughts can be unrelenting—fully-formed worries or obsessions—coming in succession again and again and again. Other times, a particularly strong thought—muscly, bullying—can take hold and not let go.

*

Along with our vague understanding of thoughts, theorists can’t agree on how emotions occur. Are emotions responses to a situation? Or do our thoughts create our emotions? Or does it all happen at once? Or does our physical state (hungry, tired, dehydrated, etc.—which emotion theorists call affect or mood) create emotions and determine how we respond to a situation?

On the most basic level, an emotion is a sensation or a series of vibrations in the body: a fluttering heart, sweaty hands, a stomachache, weak knees; a pulsing sensation in your head, a weight on your chest, the tightening of your shoulders and neck, a rush of warmth to your face. The American Psychological Association (APA) describes it as “a complex reaction pattern involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements.” Merriam-Webster defines it as “a conscious mental reaction…subjectively experienced as strong feeling…typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body.”

Emotions aren’t discrete categories. The bodily sensations we attach to one emotion can apply to another. A churning stomach, shakiness, and a rapid heartbeat could indicate anger but also fear.

Emotions occur for different reasons and produce various effects. Some emotions are passive, others active. We’re consciously aware of some while others seem to pass through us without us being able to process them. Some manifest externally (a smile, crying); others are invisible to those around us. We can spend days, weeks, months, or years experiencing some (depression, anxiety), whereas others pass through us almost instantaneously.

A behavior is obviously something we do.

Except it’s not.

Psychology identifies itself as “the science of behavior,” even though psychologists can’t agree on a definition of behavior. Is it physical movement and verbal effect? Is it a mental experience? Is a behavior influenced by our childhoods, society, biology, or all three? Does it have to be observable or can it be internal?

The big question is if a behavior’s context changes the behavior itself. Does the reason behind the action matter? Is running simply the behavior of lifting one’s feet off the ground a certain degree at a certain pace with a certain momentum? Is a person running to catch a thief the same action as a thief running to escape capture?

What about the emotion fueling the behavior? What about the thoughts driving it?

I was completely unaware of one of the most basic precepts in psychological (and Buddhist) literature: the motivational triad. It says that our thoughts fuel our emotions, which then drive our behaviors. We live in a think-feel-act cycle.

Once I understood this cycle, I developed an awareness of it. No longer did my emotions seem outside my control; they arose because of whatever I was thinking. My behaviors were no longer a mystery to me.

It wasn’t until I understood why we, as humans, think the way we do, that I was able to really heal. Evolutionarily speaking, our brains are designed to keep us alive by avoiding pain, minimizing effort, and, perhaps, seeking pleasure. I viewed racing thoughts and emotions like anxiety and depression and the behaviors that resulted from them as problematic, which made them intense and scary. I’d been trying to control, delete, and fix my thoughts, emotions, and behaviors without understanding why they occurred.

*

My father and I started having lunch together every Sunday. It became the highlight of my week. Not something the well-adjusted woman does—her social outings are voluble or intimate or peppy or all about “connecting.”

We decided to read a book together that changed my life: Randolph Nesse’s Good Reasons for Bad Feelings. Nesse is an evolutionary psychiatrist at the University of Michigan who takes an evolutionary psychiatry view of why our thoughts can be so troubling and distressing.

We used to believe the brain reacted to the world, but the brain is actually a prediction machine. During our waking hours, it sits inside our skulls, in the dark, trying to keep us alive by regulating our physical bodies, evaluating external sensations and situations, and trying to predict what will happen next by drawing on past experiences. Each prediction causes the physical sensations we call emotions which trigger an action that would best serve our bodies.

It’s a thankless job that often results in errors.

This view is fundamental to evolutionary psychiatry and its precursor, evolutionary medicine. Regular medicine is about finding a problem and fixing it; evolutionary medicine is about being curious as to why the health condition might exist in evolutionary terms. Psychiatry seeks to treat what it views as mental disorders; evolutionary psychiatry asks why those “disorders” exist and how, in some cases, they might be evolutionarily beneficial.

Evolutionary psychiatry has its detractors, but it offers a different paradigm for how the brain works. We’re all just trying to survive. The brain is out to maximize the transmission of our genes by keeping us alive—that’s it. It’s not there to make us happy. It’s not there to give us a certain “quality of life.” It’s mercenary. It’s programmed to protect us and conserve energy. We’re designed to fight, flee, and freeze to escape predators and belong to a clan when it benefits us.

In this, our negative and self-defeating thoughts are useful. Thoughts along the lines of this will never work and everything is awful are the brain’s way of warning us of possible danger. That’s its job. No one liked my presentation is the result of the brain looking for what’s wrong. Negativity is our default mode. Unwarranted thoughts like I made a fool of myself at the party and she’s mad at me come from a fear of being expelled from the clan and (evolutionarily speaking) having less access to shelter, protection, and food.

Procrastination is our brain’s way of telling us to conserve energy. I don’t feel like it and I don’t want to are ways to get us on the couch watching TV. I’ll never do it is a call to relax. Slothfulness is human.

All this would be fine, except many people—particularly those who don’t suffer from poverty and are potential victims of violence—live comparatively free of mortal threat. Extreme emotions, responses, and thoughts are natural but no longer useful. We see lions even when we’re just answering emails.

According to Nesse, negative emotions and behaviors serve a purpose, too. Emotions like anxiety and depression and even psychotic thoughts and destructive behaviors like binge eating aren’t pathological; they date back to primitive humankind and, for some reason, haven’t been eliminated by natural selection.

Anxiety (even edginess) helped primitive humans stay alert and run from lions on the veldt. A panic attack is the result of an all-or-nothing response system; we’re impalas reacting to a noise in the bush, preferring to overreact to a false alarm (a mouse scurrying along) rather than be eaten by a lion.

Depression might be a reasonable—even evolutionarily beneficial—way of responding to stress. The emotion of depression (a slowing, a weight) could be the body’s response to extended periods of the emotion of anxiety (hypervigilance, rushes of adrenaline).

Psychosis could be a defense mechanism, a mode of self-protection, or a way of escaping into an alternate reality when the current one becomes too much.

Binge eating was what we did when we lived on the savannah. If we found a bush of berries, we ate them all because we didn’t know where our next meal would come from.

Evolutionary psychiatry had what I needed: a way to see distressing emotions as normal and not as signs of a mental disorder—or even a problem. It showed me that not wanting to have a million friends or be on social media is an evolutionarily sound choice.

We aren’t designed for this world. It’s unsettling and the noisier it gets, the more demanding it becomes in terms of what and who we’re supposed to be, the sicker we will be.

To support my work, purchase or gift a copy of my USA Today bestselling memoir—and the prequel to Cured—Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses.

I search through all the muck that bogs down online platforms for intelligent, meaningful writing that addresses important topics. Well, here it is! You are a stunning thinker and writer, Sarah. You are a gift. Please, write. Write and write!

I'm so interested in this topic as a way of understanding both myself and others.

Becoming a grandparent, for example, is in one sense evolution's way of saying your services are no longer required.

We talk about a "loneliness epidemic" but you'd think that the ability to handle solitude would be a survival trait if you assume that throughout our evolutionary history there would be times in someone's life where they would be alone.

Thanks Sarah for much to think about.