Duke University's Dr. Allen Frances

Once named the most powerful psychiatrist in America, Allen Frances shares hope for recovery and dismay about the future of mental health

These interviews provide the most cutting-edge thinking on how we recover from and navigate psychiatric illness and mental and emotional distress. To make their various viewpoints clear, I ask each expert the same questions—with a few bonus questions thrown in.

Interview with Allen Frances

Once dubbed “the most powerful psychiatrist in America” by The New York Times, Allen Frances is a name you should know; he has had and continues to have a formidable effect on the way we view our mental and emotional lives. A clinician, educator, researcher, and the leading authority on psychiatric diagnoses, he’s Professor and Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University School of Medicine.

In 1994, he was chair of the fourth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—the book psychiatrists use to diagnose us. He and the other members of the various task forces made three diagnoses much easier to receive: bipolar disorder, autism/Asperger’s, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). These became ‘easier to receive’ because the criteria for each was loosened. In other words, after 1994, adult bipolar disorder, autism, and ADHD had less stringent requirements in terms of the number of symptoms, types of symptoms, and the length of time one had to have displayed symptoms to receive the diagnosis.

The result, Allen later said, was three “false epidemics”—or psychiatric fads. Pharmaceutical companies marketed them to the public for profit. (To pharma, someone with a diagnosis = a lifelong customer.) Academic psychiatrists who receive funding from pharmaceutical companies endorsed them. Patient advocacy groups publicized them, claiming they were underdiagnosed. (Some say patient advocacy groups acted with the best intentions; others would disagree.) The media hyped the diagnoses (Does your child have ADHD?). Clinicians started to see them more readily in their patients. (These clinicians likely wanted to help their patients.) People started to see these diagnoses in themselves and their loved ones. The fads took hold and haven’t let up.

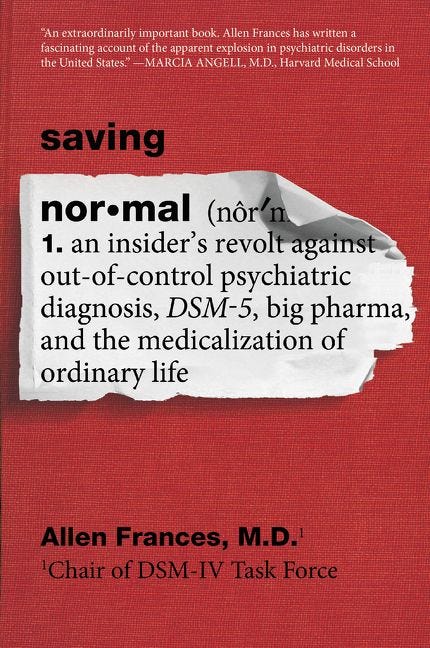

In 2014, Frances published an apology in the form of a book every American who’s in the mental health system or whose loved ones are in it should consider reading: Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life. The book—and the op-eds and blogs Allen published in the years leading up to it—rocked the psychiatry world. The one-time most powerful psychiatrist in America was warning the American public about the diagnoses we receive—diagnoses he helped create.

I was fortunate enough to appear at the Mad in Brasil Conference with Allen, during which he encouraged psychiatry to adopt the bio-psycho-social model of mental illness. Instead of assuming that mental and emotional distress are purely biological, we need to consider the psychological and social factors as well. (That’s a very simplistic summary of it.)

He also addressed how clinicians should be diagnosing patients today: with care and restraint. As Allen put it, “I probably know the most about diagnoses, and I’m probably the most conservative in giving one.”

Frances was kind enough to answer my questions about recovery and the future of mental health.

Read on…

What does recovery from mental illness mean to you?

Psychiatric treatments too often focus only helping to reduce symptoms, neglecting the equally important goals of preventing recurrence; understanding the person’s past and current life circumstances; planning for the future; creating new support systems; promoting hope; reversing demoralization; increasing resilience and self-efficacy; and finding meaning in life. ‘Recovery’ to me follows the Hippocratic dictum: “It is more important to know the patient than to know the disease” and seeks to help the whole person—not just treat symptoms.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about recovery?

That one size fits all and there is only one right path to follow to greater happiness and health. Recovery comes in many forms and each person has to find what works best for them.

What about the future of mental health care makes you most hopeful?

Not much. Mental health care in the United States is radically underfunded, ridiculously disorganized, and politically unpopular. The U.S. is the worst country in the developed world for people with severe mental illness—650,000 are forced to live in prison dungeons or rough on the streets. This won’t change until we as a country commit to providing adequate community treatment and decent housing. Things are worse now than when I began practicing psychiatry 50 years ago— and I detect no signs that they will get better in the future.

If there was one thing you could say to people who are struggling with psychiatric illness and mental and emotional distress, what would it be?

Never give up hope and never stop trying. Often, even small positive changes in your life can, via positive feedback loops, reverse vicious cycles of despair and create virtuous cycles of recovery.

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber for $30/year, the equivalent price of a hardcover book.

Visit the Table of Contents and Introduction of Cured:

Find more resources for mental health recovery.

Read the prequel to ‘Cured,’ ‘Pathological’ (HarperCollins):