Why Where You Live Determines If You Recover from Mental Illness

The environmental factor we ignore

For those on the go, I read this to you here ↑

I’d been living in a tiny studio apartment that looked out onto a brick wall. Now that I’d advanced far enough along in my recovery to be able to advocate for and do things for myself, I determined to move. The apartments were either too expensive or dilapidated; there was no in-between.

One apartment seemed promising though the photos were all taken at night, making the rooms seem small and a little dismal, which might be why it was available. A friend of the owner showed me the apartment.

It was late dusk. The moment we entered, I was home.

It was palatial in comparison to my brick-wall studio: 720 square feet. The open floor plan made me want to run through it. (I didn’t.) The kitchen had all new appliances. They gleamed. There was a dishwasher—something I’d never had. The rest of the main room had space for a small kitchen table and chairs, a sofa, and my desk. The bedroom area was sectioned off.

Then I saw it: the balcony. I walked toward it. It was brittlely cold out, so I didn’t open the sliding glass door. In the distance was the skyline in full view. No brick wall. The city lights flickered and danced—mostly because I wasn’t wearing my glasses but still, they danced.

The other best part: It was quiet. Not a sound from the surrounding apartments like in my studio. No bass thumping through floorboards.

I made an appointment to see it again the next day.

Most of my family came with me. The agent showed us in. I followed my mother, stepmother, and father around the apartment, trying to gauge their expressions.

The four of us stood at the sliding glass door. The winter sky was flawlessly blue. The skyline stood strong. I could see the lake—pewter blue and still—the same lake I once thought of drowning myself in.

My stepmother said it first: “This was a great place.” My father nodded. My mother smiled.

My illness had taken a toll on them. It led to periods of caretaking and strain, tension and distance. Having them there was almost as important as having found a place to live.

My mother helped me move in. For five years, I lived with her in her apartment. We turned the room she used as a study/office/den into a makeshift bedroom. One year became two, then three, then four. Five years of her as my caretaker—dealing with my moods and anxieties and compulsions and depressions, going to the emergency room with me, being on suicide watch. Too much to ask, especially of someone without the emotional support family members and caregivers needed and deserved.

She unpacked the dishes and took them out of the newspaper. I shelved books and set up my computer.

After an hour, she surveyed the main room and said, “You look like you’re in good shape. I don’t think you needed me anymore.”

She meant that afternoon, but the words—in all their meaning—made my stomach do a little flip with what must have been excitement or pride. It was true. I didn’t need her the way I once did.

We walked to the door and hugged. For the first time, we hugged each other equally.

My new couch was against the wall, just where it should be. In the bedroom, my bed was made. My desk was set up for me to write tomorrow morning.

At dawn, I woke and rushed to the balcony and stood at the sliding glass door. Fog had rolled in off the lake. I was high enough up—the twenty-sixth floor—so that I was above it. There was only blue sky and fog below.

I got my phone and took a picture.

Every morning for the next year I’d do the same, photographing pink sunrises; white, puffy cumulus clouds; orange sunsets; heavy clouds of pewter grey and the faintest blue—it didn’t matter. I photographed them all. One late afternoon, I captured a whole rainbow, end to end.

The history of how we’ve treated and housed those with mental illnesses is inexcusable, particularly the nineteenth-century asylum system.

Although the word asylum may bring to mind images of half-clothed, raving “lunatics” chained to walls, it means sanctuary.

Select early asylums were true to the actual meaning of the word. They functioned as retreats. As Yale researcher Larry Davidson and his colleagues have shown, they boasted astounding recovery rates.

Between 1813 and 1843, retreats reported recovery rates between 70 and 90 percent for those patients who’d been admitted within the first year of experiencing a psychiatric crisis. (Let that sink in.) Overall, the recovery rate was between 45 and 65 percent. (Though some scholars contend that these percentages are too high, in the 1950s, Davidson cites studies that have confirmed these numbers.) In 1881, one public asylum, Massachusetts’ Worcester Asylum for the Insane, surveyed over a thousand patients who’d been discharged and found that 58 percent had not experienced mental illness again.

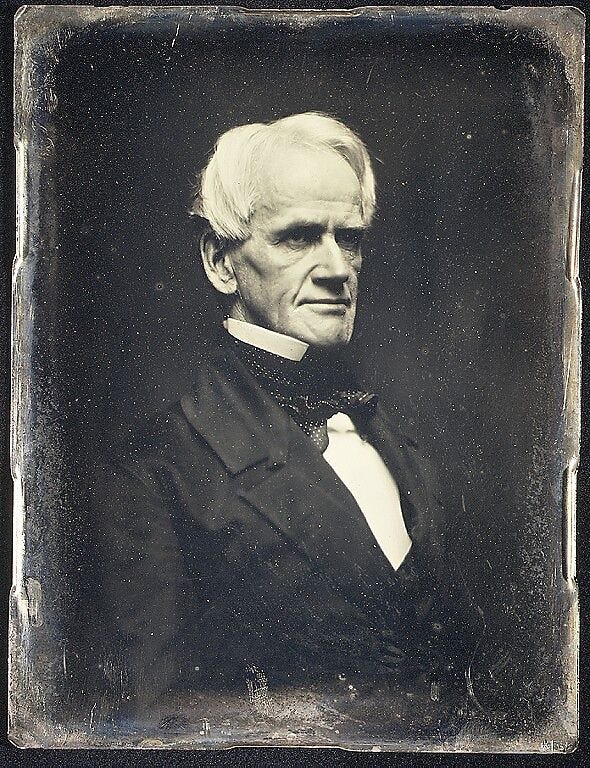

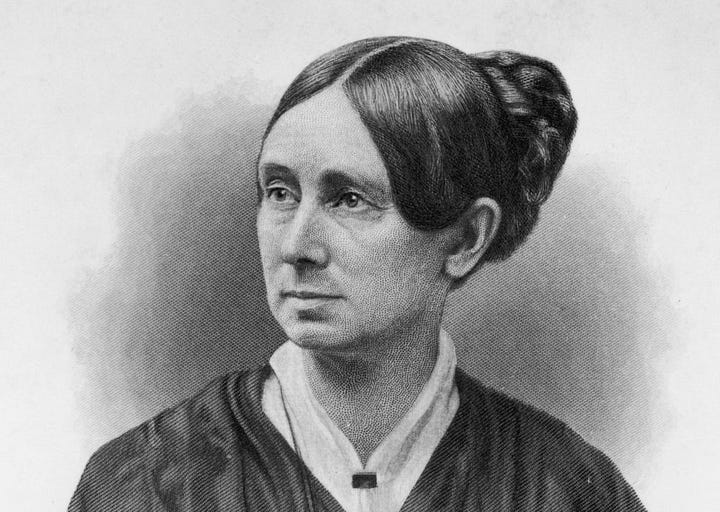

Several asylum superintendents—later called alienists and then psychiatrists—claimed that under the right conditions, the insane could recover their sanity. (Mental illnesses fell into two categories: insanity and idiocy though the terms were often used interchangeably.) This was a bold claim. Patients typically included the most severe cases of mental illness, alcoholics, the elderly suffering from senility, and syphilitics. Enthusiasts like mental health advocate Dorothea Dix, politician Horace Mann, and the heads of the Ohio State Asylum and the McLean Asylum in Boston insisted that mental illness was entirely curable through moral and humane treatment.

The “cure” for mental illness had everything to do with where the patients were housed.

The architect, physician, and mental-health advocate Thomas Story Kirkbride designed asylums that offered patients fresh air, beauty, privacy, and comfort. The center structures of his buildings proudly faced out, and the wings let in fresh air and natural light. They housed museums, libraries, and workshops. Patients had their own rooms, which had twelve-foot ceilings. They sometimes tended the lush grounds themselves.

Mental hospitals, Kirkbride said, should impress the patients and inspire faith in the psychiatric profession.

Retreats offered patients idyllic environments in which to heal. But these retreats were private and very expensive. They housed twenty-five or thirty-five patients and didn’t extend care to the majority of those in need.

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, the number of public asylums increased, as did the number of patients crowded into them. Some, which once housed less than fifty patients, had over two thousand patients. Living conditions were revolting and inhumane.

Hospitalization is still the primary treatment option for those in psychiatric crisis, but the question as to whether people should be removed from their everyday lives to receive care is hotly debated. Davidson and others argue that removing patients from the community—whether to a retreat, an asylum, or an inpatient psych ward—doesn’t help the patient recover. (The question of whether inpatient programs are or are not useful in psychiatric crises and emergencies depends on which activists and scholars you consult.)

He refers to the influential sociologist Erving Goffman, who wrote in 1961 that hospitalizing a patient was akin to saving someone who can’t swim and is drowning in a lake, teaching the person to ride a bicycle, and putting the person back in the lake.

Although the issue of inpatient versus outpatient treatment often concerns those with serious mental illness, recent studies confirm that environment greatly impacts everyone’s mental health. Psychology professor Anthony Mancini discusses the critical role of “the external environment in facilitating the internal conditions of recovery” today. Recovery can’t be brought about by will. He writes, “[I]t must be facilitated by factors external to the person. Unfortunately, these facilitative conditions are typically in scarce supply for people with serious mental illness, in large measure because such illness puts them at risk of being in environments that are suboptimal for healthy functioning.”

The morning after I moved in, I went for a walk, passing the building just north of mine. It was run down. Small windows looked out onto the street, but the windows on either side of the building looked out onto brick walls.

Outside the building stood a group of mostly men, not together, each on their own, all smoking. One muttered to himself. They stared dazedly at the cars passing.

I recognized them, not personally but as people with mental illnesses. Maybe it was a stereotype. Maybe I saw myself in them.

At first, my stomach lurched. I didn’t want to be close to it, didn’t want to be reminded of how I was before my recovery—as if it was contagious.

Then came a shift. Even with healing and a view, I was one of them and always would be. Oddly, my chest swelled with a sense of connection.

The small plaque on the side of the building that read Clayton House confirmed my first impression. A Google search on my phone told me it was a transition home for people with serious mental illness.

When I came back, they were gone. The only difference between them and me was privilege and opportunity: healthcare, eventually finding a good psychiatrist, family support, healthy food, medications with low-side-effect profiles, no co-occurring addictions, and a life filled with purpose in the form of writing and teaching. I had what was needed to heal; they and so many others did not.

How can we expect people to recover from psychiatric disorders—especially those who’ve been struggling for decades—without giving them a safe, supportive environment to do it in?

When it comes to regaining mental health, where we live determines if we heal. The four dimensions of recovery as outlined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) are health, purpose, community, and home.

Home is the big one. It sits prominently on psychologist Abraham Maslow’s list of basic human needs—home, income, food, safety, and companionship.

Place and recovery: it’s so obvious, yet we’ve done little to create environments for people with mental illness, so they can heal.

As the psychologist and mental health innovator Patricia Deegan, who fully healed from schizophrenia, says, “Stop asking what’s wrong with people with mental disorders and instead ask, ‘How do we create hope-filled, humanized environments in which people can grow and fulfill their human potential?’”

In a meta-analysis of the scientific literature on environment and mental health, researchers analyzed the importance of each aspect of our surroundings.“Hominess” has been found to decrease patients’ physical and emotional pain. Unsurprisingly, views of nature, gardens, and indoor plants can increase positive emotions and lessen negative ones. Natural lighting encourages healing and increases positive thoughts. Ambient chaotic noise, like that found in hospitals, creates stress. A space free of distractions (i.e., phones off, focus time on) contributes to productivity and calmness. Feeling safe and having privacy matter. Color affects mood though the internet is a hotbed of conflicting information on just which colors create which effect.

But the most significant factor is if you have a view. Greenery is best but even being able to see a concrete sidewalk with people on it or a dirt road on which a car might pass is crucial to mental health and healing.

Place.

A view onto something.

A physical view: the physical equivalent of having a future.

Dr. R crossed his leg in a figure-four, bobbed his head. That was that.

The best way to support my work is to purchase a copy of my national bestselling memoir Pathological, hailed by The New York Times as “a fiery manifesto of a memoir.” Pathological traces how we’ve come to believe that ordinary emotions are mental disorders and the twenty-five years I spent in the mental health system believing that psychiatric diagnoses are valid and reliable, which they’re not. If you’ve already purchased a copy, thank you! You can gift a copy to a friend, your local library, or your favorite used bookstore.

I’m going to try to spend more time outside. I do get very depressed each winter. Maybe being outdoors will help!

Surroundings are most important, but i get so involved in my work that i don't give a thought to anything, but what i am doing....learning, writing and sharing. I have been there and done that, and learned from the experiences. I get so involved in what I am doing I lose track of time. I have no time to think about anything else. It has got me into trouble, because I have forgotten in the past to eat or sleep. Then, after awhile, i would detach and just want to stay in bed. Then, my family would put me into a mental hospital, which was not a healthy asylum. i would be treated with toxic mind destroying drugs, instead of nourishment for the brain. The most important things for mental health: Nutrient-rich food for the brain, adequate hours of deep sleep, daily sunshine, fresh air, exercise and knowing you are never alone...the Creator is always with you.