What's the Best News About Mental Illness You May Not Have Heard?

This post is in honor of Mental Health Awareness Month

Answer: Read on.

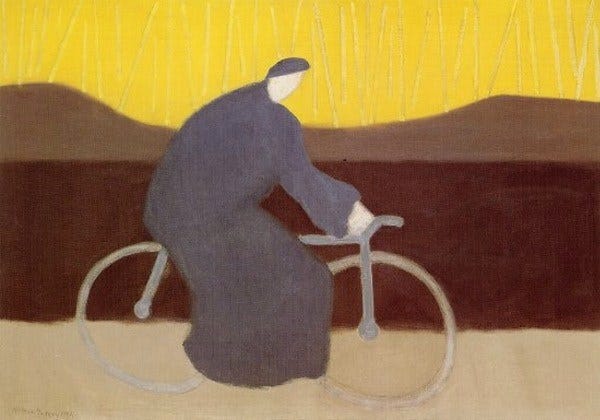

I was biking home in the rain the evening I decided to file for disability. My jacket was soaked. Wet autumn leaves blanketed the city streets. I didn’t have my glasses on, and the stoplights blurred. Earlier that day, I’d discussed the possibility of going on disability with my psychiatrist. He said it was worth considering. I was in my forties and unable to live independently due to a lifelong, serious mental illness: bipolar disorder. According to him, my life would consist of manic highs and depressive lows. Suicidality would come and go. I’d never be fully well.

I’d heard this before, albeit about other diagnoses. Starting when I was twelve, I was diagnosed with anorexia, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and bipolar disorder. I was told that each was chronic—as is the case with many of the 46 percent of American adults and 20 percent of American children and adolescents who will receive a mental disorder in their lifetimes,

Finally, I made it home to my mother’s apartment. I’d been living there for four years, unable to live independently. The apartment was warm. I called, “Hello,” and took off my dripping jacket. My mother greeted me and asked me how my appointment had been. I quickly told her of my plans to file for disability. She said she supported me in whatever decision I made.

After changing out of my wet clothes, I went to my computer and pulled up the Social Security Administration website. I qualified for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), but one question on the form stopped me: Did I have a medical condition that would last at least twelve months or result in death?

The answer was yes, wasn’t it? I’d always “be” bipolar, wouldn’t I?

At the time, I thought I would, but I didn’t end up filing for disability. Ultimately, I decided that it wasn’t right for someone like me to take such a valuable resource from someone who needed it more than I did. (SSI is hard to get and even harder to keep.) My part-time job teaching adjunct at two universities was manageable. My family gave me tremendous support, and I had health insurance.

I ended up seeing a new psychiatrist for reasons that had nothing to do with filing for disability. During one of our sessions, he told me about one of his patients. She had “fully recovered” from schizoaffective disorder (a serious mental illness often described as bipolar disorder with hallucinations and delusions) and was now an executive at Google.

Over thirty years, not one of my doctors had spoken the word recovery. My primary care physicians and psychiatrists never once mentioned that I could get well.

The falsehood that mental disorders are definitively chronic is all over the internet, but there is no evidence that the diagnoses we receive are lifelong. Even when we’re granted the possibility of recovery, we’re told that the most we can aspire to is remission. Our disorders will always lurk below the surface. We’ll always be someone with a mental illness.

There may be good reasons not to publicize that mental illness isn’t chronic. We don’t want people suddenly going off their medications or not getting the support they need. We also don’t want those with anosognosia—a neurological condition that often afflicts those with serious mental illness in which one denies one is ill—to assume they’re well. But imagine if we told cancer patients that they would always have cancer? How many of them would be restored to health?

The words fully recovered started me on a bumpy, sometimes harrowing road to mental health. I suffered intensely, but with those words, my suffering changed. I had hope.

Even after I recovered, I told others and myself that I “had or have” a mental illness. I didn’t feel comfortable saying I’d been cured. There isn’t a cure for mental illness. We don’t have a pill or a magic bullet. But I’m living proof that we can cure mental illness. The definition of the verb to cure is “to restore to health, soundness, or normality” and “to bring about recovery from.”

What are health, soundness, and normality? It will look different for each person. It may mean continuing to take medication and seeing a psychiatrist. (I still do both.) It will mean having uncomfortable, painful emotions for extended periods; behaving in ways we’d rather not; and being besieged by negative thoughts. That’s part of the human experience.

Last week, Thomas Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), published Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health. He writes that mental illness, even serious mental illness isn’t chronic. During his time at the NIMH, he was known as “America’s psychiatrist.” Insel is clear that full recovery takes what he calls “the three p’s”: people, place, and purpose. (I had all three: a family that supported me, my mother’s apartment in which to heal, and my writing.)

Full recovery will require giving people with mental illnesses hope. Clinicians and mental health professionals must offer patients the opportunity to be well by telling us that it’s possible. Those of us fully restored to health need to let others know. We need to be proud survivors of mental illness, the same way those who have battled and won the fight against cancer are.

In an interview, Insel likened having a mental illness to breaking a leg. It can be debilitating, but it can heal. Some may feel and demonstrate lingering effects—chronic pain, a limp. Some may always need physical therapy. Other issues may arise because of the break. Having broken a leg may feel like a weakness. But, as Insel explains, medically speaking, after the bones are rejoined, the point of the fracture is the strongest part.

Support independent journalism. Readers like you make my work possible. Get the annual discounted subscription for $30/year—the equivalent of purchasing one hardcover book.

You can buy my memoir, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins), here: