Is There a Misinformation Effect in Mental Health Memoirs?

Answer: Yes.

Most of my misconceptions about my mental health diagnoses came from television, film, pop culture, and books. Lots of books. Over the years, these books—particularly mental-illness memoirs (a subgenre all their own)—told me that those of us with mental illnesses are violent, extreme, and/or immature. They made it seem like we bounce in and out of desolate, chaotic mental hospitals and portrayed us as pill-popping victims of the mental health industrial complex.

These books taught me that the mental health diagnoses I’d received were valid and reliable, as medically sound as cancer diagnoses. I was given six in total, starting at age twelve: anorexia nervosa, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and bipolar disorder. Like the 46 percent of American adults and 20 percent of American children and adolescents who will receive a mental health diagnosis in their lifetimes, I didn’t know that the diagnoses we receive aren’t born of scientific discoveries or refined according to hard data; they’re theories written in a book: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

The DSM’s legitimacy has been questioned time and again. DSM diagnoses have been found to be “scientifically meaningless.” No DSM diagnosis is valid, i.e., no test or biological marker can confirm that anyone has a DSM diagnosis. More shocking than that (at least to me—I found all this out after diagnosis number six), they’re merely a collection of symptoms hypothesized by the DSM authors, i.e., mental health professionals, many of whom have ties to big pharma (69 percent at last count). DSM diagnoses don’t have clear cut-off points to measure normal versus abnormal. DSM diagnoses haven’t been shown to be genetic or chronic. They’re based entirely on self-reported symptoms and the opinion of a clinician. They’re rarely reliable, i.e., two clinicians can’t consistently diagnose the same patient with the same disorder. The DSM has been referred to not as a scientific manual but as a cultural relic shaped by bureaucracy; the influence of big pharma; and the desire of its authors to medicalize everyday behaviors, thoughts, and emotions. (The two exceptions to all of the above are dementia and rare chromosomal disorders.)

Memoirs about mental illness fail to provide readers with these truths and warn them against blithely giving, receiving, and identifying with invalid mental health diagnoses. These writers (I assume) do so out of ignorance, not duplicity. But that doesn’t make their books any less hazardous to those seeking truthful answers for their emotional and mental suffering.

(To be clear, although DSM diagnoses are questionable, mental illness is very, very real. I had or have a mental illness—“had” or “have” depending on whether you want to believe mental illness is chronic, which it hasn’t been confirmed to be.)

My miseducation of mental health diagnoses started in my twenties with depression and William Styron’s Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (1989). Darkness Visible is a raw, beautiful, harrowingly understated memoir. Though at the time it was written, men rarely spoke about their mental health struggles, Styron lets us in on his darkest moments. I read the book in nearly one sitting.

He writes movingly of his depression diagnosis—and gives us false information about it. He taught me that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance, was chronic, and often ends in suicide—none of which are true. He calls depression a disease, which it isn’t. To call a condition a disease, physicians must be able to give a patient a relatively clear sense of a diagnosis’s cause, symptoms, treatment, and prognosis—none of which we have for mental health diagnoses like depression. With certainty, Styron writes that depression is a biochemical malfunction resulting from “systemic stress” amid “neurotransmitters of the brain” that cause serotonin depletion. The rates of suicide are troubling with diagnoses of depression (7% to 10%), but those diagnosed with bipolar disorder are far more likely to end their lives (15% to 30%).

Styron wasn’t intentionally misleading readers. Clearly, he believed his diagnosis was valid and reliable. He speaks with reverence of the DSM. Plus, Darkness Visible was published over ten years before the controversies surrounding the DSM crescendoed in 2013. But the misinformation in Darkness Visible is still available to readers like me looking for solace, even help.

I read Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind (1995) two years before I received my bipolar diagnosis. The memoir starts with Jamison as a medical student at Stanford. It follows her as she finally comes to terms with her bipolar disorder diagnosis and lands a job on The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine faculty. Jamison writes of her manic-depression tenderly, almost lovingly. (She prefers that label to bipolar disorder, believing that the term manic-depression is more illustrative of the highs and lows said to be inherent in bipolar disorder.) She describes having a sense of flying and touching Saturn during her manic highs and falling into “lacerating,” black moods during her suicidal depressions. To Jamison, DSM diagnoses aren’t to be interrogated or even shied away from. They’re romantic, even glorious, the stuff of genius and creativity.

Nothing would have made me question Jamison’s authority. She is—and was—on the faculty of one of the best medical schools in the country. She is—and was—a co-author of the classic textbook Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression, which is still taught in medical schools throughout the US. Even someone well aware of the DSM’s crippling flaws—which I wasn’t—might have thought, Well, she must be right.

At one point, Jamison admits that studies claiming to unearth neurological causes of mental illness raise “more questions than answers,” but it’s just a matter of time before psychiatry catches up with science. She writes, “once genes are located” (emphasis mine) rather than if they ever are. Jamison repeatedly calls manic-depression a “disease” with biological underpinnings, although no such evidence existed. Nor does it now. In the nearly thirty years since An Unquiet Mind was published, psychiatry hasn’t come close to substantiating the biomedical model it says underpins all DSM diagnoses.

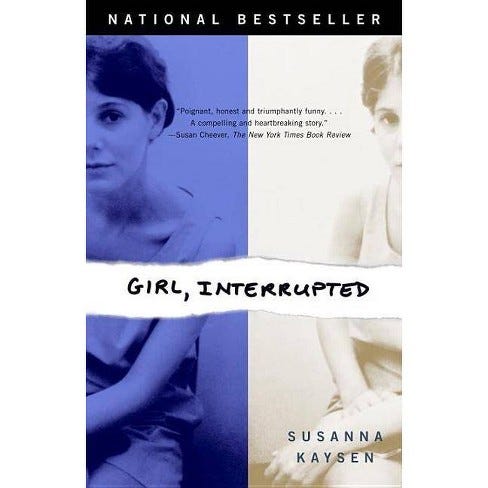

I was never diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) described in Susan Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted (1993), but the book affected me. The memoir tells of her experience as a teenager at a preeminent psychiatric facility, McLean Hospital, in the 1960s.

Readers of Girl, Interrupted would be hard-pressed not to take her claims about her diagnosis of borderline personality disorder as anything other than factual. By including images of her actual medical records, Kaysen seems to “report” on her diagnosis as someone who knows based on first-hand experience. Kaysen questions the integrity of the DSM—albeit briefly. She acknowledges that DSM diagnoses—like homosexuality—are dropped and added based not on scientific discoveries but due to political and social pressure. But she ends by confirming her diagnosis in the pages of the third edition of the DSM as if it is, in fact, gospel.

After reading the DSM-III, Kaysen claims that her diagnosis is the scientifically proven result of the mind “interrupting” the chemical wiring of the brain. BPD didn’t exist when Kaysen was at McLean. It was first a syndrome, then a disorder, and didn’t become a full-fledged DSM diagnosis in the DSM-III in 1980. In 1967 and 1968, the hospital staff would have viewed most mental illnesses as neurotic responses to life events—not “brain diseases” and how Kaysen describes them. The list of supposed symptoms Kaysen identifies with—instability, extreme attachment to others, fears of abandonment, all-or-nothing thinking, and emotional volatility—is based on no scientific data, only on the supposed usefulness of letting clinicians diagnose patients they couldn’t otherwise diagnose. Yet she finds an explanation for her mental and emotional suffering in the DSM. (Kaysen hasn’t commented on that aspect of the book though she has expressed her dislike of it for other reasons.)

I didn’t read Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation (1994) until after I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, but it also gives the DSM undeserved credibility. Surprisingly little of Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation is actually about the antidepressant Prozac. The drug only appears as the deus ex machina at the end of the book, finally saving her from her attempts to self-medicate with alcohol and illicit drugs. Most of the book is about her diagnosis of atypical depression.

Wurtzel establishes authority by citing statistics; using medical language; and implying that her diagnosis is genetic and biological. She notes that fewer than 40 percent of people diagnosed with depression meet the DSM criteria, but that doesn’t stop her from unquestioningly accepting the diagnosis. The doctors at McLean are declared “diagnosticians.” She misinforms the reader that “clinical depression is a disease, one that not only can but probably should be treated with drugs.” This gives her “some kind of hope.” As further validation of her diagnosis, Wurtzel asserts that depression runs in her family, implying that it’s genetic.

Prozac Nation encourages self-diagnosis and sets a very low bar for giving oneself a diagnosis of atypical depression. Wurtzel claims that if you’re existentially troubled by life as a teenager, tired a lot of the time, overeat or oversleep, and experience mood swings (even merely cheering up in response to positive events), even if all of these “symptoms” are likely a result of drinking to excess and bingeing on recreational drugs, you could have atypical depression, too. As charming and snappy a writer as Wurtzel is, her diagnosis allows her to avoid looking at other possible causes for her suffering, e.g., her astonishing solipsism, drug use, and profound immaturity.

There is one moment in the book when Wurtzel almost questions the validity of her diagnosis. She’s troubled when she learns that “atypical depression, like many DSM diagnoses, is illogically legitimized by the medication prescribed for it.” The psychotropic-drug-as-proof-of-disorder fallacy is one of the most popular ways some psychiatrists and researchers try to validate DSM diagnoses. The assumption was—and is—that if the pill we’ve named an antidepressant, e.g., a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), can treat someone diagnosed with depression, then the person must have depression. Wurtzel explains away her doubts by saying that “this is a typical course of events in psychology.”

Fiction may have contributed to my romanticization and stigmatization of mental illness, but I don’t remember reading about particular DSM diagnoses. For example, we never learn McMurphy’s diagnosis in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. But one novel taught me how to become my DSM diagnosis.

Until I read the anorexia urtext Steven Levenkron’s The Best Little Girl in the World at sixteen, I was a teenager who had a stomach ache and didn’t—couldn’t—eat for situational reasons. My parents were divorcing, I was going through puberty, and I was attending a new high school—all good causes for a seemingly permanent stomach ache. Although a work of fiction, The Best Little Girl in the World became an instructional manual and cheat sheet on how to be an anorexic. It long predated pro-ana websites and thinspiration hashtags but to a similar effect. (Levenkron wasn’t a writer; he was a psychotherapist. He unsuccessfully treated the singer and drummer Karen Carpenter.)

The novel follows Francesca, a teenager who renames herself Kessa to signify her transformation into someone thin and in control and stops eating until she ends up in the hospital with a tube in her jugular force-feeding her. Kessa taught me to identify myself as an anorexic. From her, I learned to arrange my food on my plate, so it looked like I’d eaten and to create rituals around food. (She cuts her toast into halves and then quarters and eats a quarter at a time while tapping her fingers on the side of her chair and silently chanting her name to four syllabic beats, four being the “magic number” that will keep her from gaining weight.) I trained in the arts of lying to therapists and eating just enough to stay out of the hospital, a task Kessa fails at.

Levenkron never talks about the validity of Kessa’s diagnosis or the DSM, but (much the way many eating-disorder memoirs do) he structures the novel so that anorexia remains the goal achieved in the protagonist’s quest. Kessa’s descent into anorexia is clearly plotted; her ascent out of it occupies a scant thirty-five of the book’s two-hundred-fifty-two pages. At the end of the novel, it’s still uncertain if Kessa will end up in the hospital as a result of not eating again.

Levenkron’s novel is an exception; memoir bears a particular resemblance to testimony—whether the book carries the truth or its author intended to perpetuate falsehoods. Girl, Interrupted and Prozac Nation were written a decade before the DSM-5 uproar, much like Darkness Visible.

Jamison’s spin in An Unquiet Mind feels more deliberate. As a professor of psychiatry (she doesn’t have a medical degree but holds the title at Hopkins), she knew the flimsiness of DSM diagnoses and could have explained them to readers. Though it’s still hard to believe malice was involved. Despite its lack of evidence, Jamison proselytized the biomedical model of DSM diagnoses.

Although An Unquiet Mind; Girl, Interrupted; and Prozac Nation were published in the 1990s, they’re still very much in the conversation. Today, 1.5 million copies of Girl, Interrupted are still in print in the U.S. Prozac Nation was a bestseller and sold over a hundred thousand copies in a single year when it was reissued in 2002 in tandem with the movie starring Christina Ricci. Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind is billed as a classic.

The question is, what do we do with memoirs that contain inaccurate information. Should publishers add disclaimers? Should we ask Kaysen and Jamison to write new introductions explaining the controversies and doubts surrounding the DSM? (Wurtzel passed away from cancer in 2020.) Would we then have to rifle through every mental-illness memoir written and fact-check them too? Maybe—and maybe that wouldn’t be a bad thing.

Support independent journalism. Readers like you make my work possible. Get the annual discounted subscription for $30/year—the equivalent of purchasing one hardcover book.

You can buy my memoir, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins), here: