What Does Eighteenth-Century Paris Have to Do With the Cure for Mental Illness?

Answer: Everything

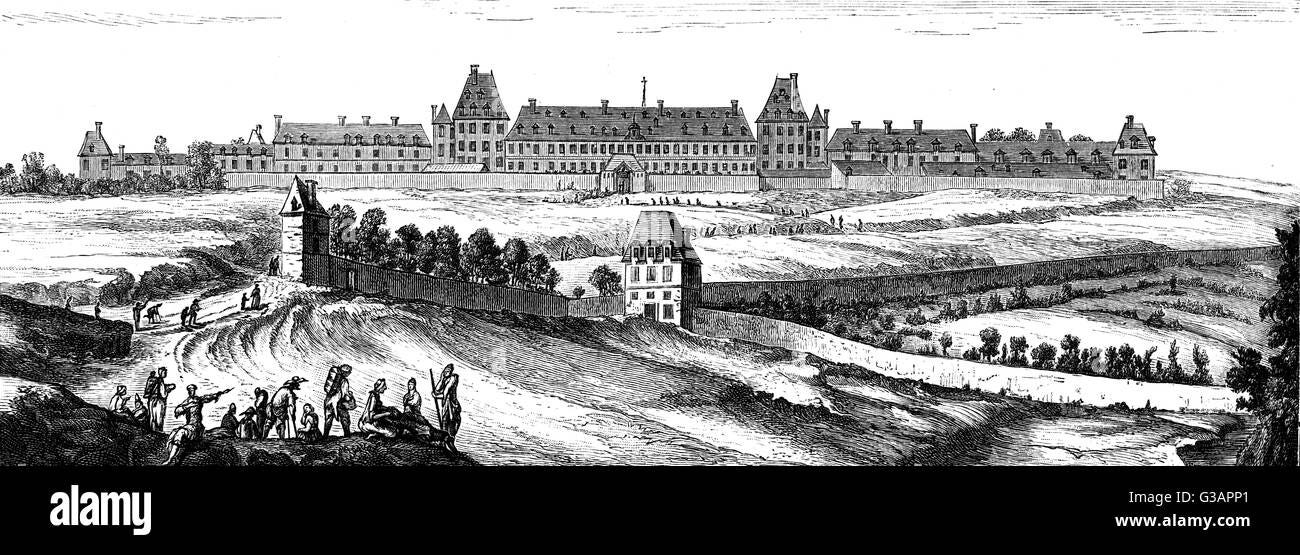

I like to picture the Hospital Bicître in Paris. Though taken much later, the above sepia-toned photograph comes to mind: the cobblestone path leading to the arched stone entrance, the stone buildings stretching past the gates.

A century earlier, it looked more like a rural prison, which it was—in part.

It was part prison, part housing shelter, part mental asylum. Most patients were afflicted by dementia, syphilis, or paralysis.

In most asylums, “lunatics” were typically divided into aggressive and non-aggressive. They were physically abused and not given clothing. The first line of treatment involved chaining them to walls.

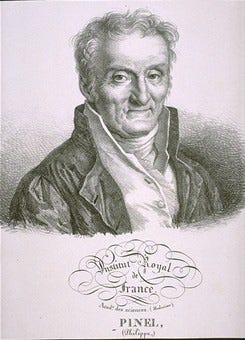

That’s not what I picture because patients in the Hospital Bicître circa 1797 were freed thanks to two men: Philippe Pinel, a physician, and Jean-Baptiste Pussin, governor of the hospital.

Pinel is credited with having liberated mental patients, for which he’s now often referred to as “the father of modern psychiatry,” but he learned from Pussin. As governor, Pussin found that patients fared better when (surprise!) they weren’t chained to walls.

I shouldn’t think so highly of Pinel and Pussin. Patients were still put in straight jackets and isolated. But the two men revolutionized how people with mental illnesses were viewed. Since the Middle Ages, the insane had been seen as degenerate, demonic, bestial, and alien. Pinel and Pussin changed that.

Pinel and Pussin thought of them simply as people suffering from mental and emotional distress. People with mental illnesses were ordinary human beings, albeit more sensitive to the world than others (qualities we sometimes value in artists and other “creatives,” as they’re now called), with rights like anyone else. Pinel and Pussin pushed for holistic care and developed traîtement moral—not to be confused with moral treatment, which came later in the U.S. and England. Traîtement moral had nothing to do with morality (right and wrong, good and bad); it asserted that those with mental illnesses (surprise!) shouldn’t be abused and should receive psychological care.

It worked. The hospital boasted a cure rate of 90 percent if—and this was a big if—patients were not treated at another hospital first. Why?

Because Pinel and Pussin knew that physical abuse and the emotional toll of being denied your human rights and told you’re beyond help compounds mental illness and leads to further deterioration. We worsen not because we have a mental illness but in response to how we’re treated.

Psychiatrists today don’t like the word cure, but curing mental illness isn’t the same as boasting of a cure. Cure comes from the Latin curare, meaning “to take care of someone.” It wasn’t until the Middle Ages that cure was associated with medicine and used as a noun to mean a remedy. There’s no single cure for mental illness—no pill or magic bullet. The definition of the verb to cure is “to restore to health, soundness, or normality.” Those categories (health, soundness, or normality) are abstractions determined by each person and culture.

Traîtement moral was rooted in the belief that patients could not only be cured but cured so entirely that they could return to the hospital and be employed to help others heal—an early example of what’s now called peer support. Pinel hired ex-patients to work at the hospital. Once again, Pussin did it first; he’d once been a patient at the hospital before he became governor, albeit for tuberculosis.

(The idea that wellness is determined by whether someone can work touches on Richard Roy Grinker’s argument that the stigma against those with mental illnesses is the result of capitalism. According to Grinker, discrimination stems from biases against the disabled because some don’t have a full-time, traditional job. His book Nobody’s Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness is well worth reading.)

In the scientific literature, Pinel introduced three pivotal truths that we still have trouble accepting some two hundred years later. Professor of Psychiatry at Yale Larry Davidson and his colleagues outline them in their excellent history of people healing from mental illness over the past two centuries, The Roots of the Recovery Movement in Psychiatry:

anyone can develop a mental illness;

mental illness occurs in response to external events (it’s not solely biological); and

it’s not all-encompassing, i.e., even in an acute phase, it merely influences a person’s perceptions, judgments, ideas, and reasoning (it’s not the whole person).

Think about it.

We still believe that only certain people suffer (read: the weak, the biologically flawed, etc.).

The chemical imbalance myth (yes, it’s a myth) and the biomedical model of mental illness continue to reign supreme.

Some people adopt diagnoses as identities as if having depression or anxiety or ADHD or schizophrenia infuses every part of them and their lives instead of being just one aspect of it.

Traîtement moral showed that mental illnesses can be episodic and aren’t necessarily chronic, something many clinicians still don’t either know or simply don’t encourage. Healing depends on restoring hopefulness to patients, yet from the most stigmatizing to the least, diagnoses are believed to be forever. “Symptoms” like depression and irritability and distractibility and anxiety and obsessions and compulsions, which are part of the human condition, supposedly represent a catastrophic brokenness in the brain. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) frames major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, ADHD, OCD, bipolar disorder, and other diagnoses as “common” and likens them to heart disease or diabetes, implying they’re inevitably chronic, which they aren’t.

How can we heal if clinicians don’t encourage us to do so?

It turns out that very little encouragement is needed to create conditions for healing—not just in mental health but in all areas of health. A 2018 study conducted by Stanford psychology Professor Alia Crum and her colleagues showed that a few comforting words from a physician speed healing. In the study, participants who were told that their allergic reaction would start to diminish and their symptoms would go away experienced relief and less itchiness than those participants to whom the doctor didn’t speak. Reassurance from a clinician induces the placebo effect, in which a person’s mindset influences recovery outcomes. A lack of support can produce a “nocebo” effect, in which a negative outlook leads to deterioration.

All we need is a word: possible. It’s possible to heal and create the life that’s best for us. Just maybe. Just the truth.

For more on what we should be talking about, i.e., mental health recovery, read Cured: The Memoir.

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber for $30/year, the equivalent price of a hardcover book.