What Does It Mean to Fear Death?

What Does It Mean to Fear Death?

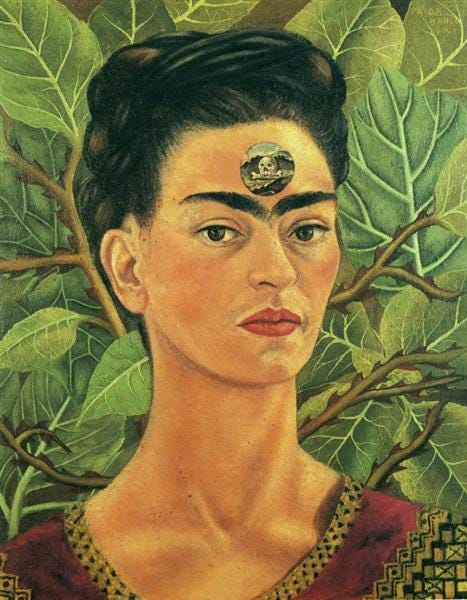

In psychology circles, death anxiety is called thanatophobia. Freud coined the term in a two-part 1915 essay, Thoughts for the Time on War and Death. He named it after Thanatos, the Greek god whose job it was to let mortals know it was their time to die. It’s strange that Freud wouldn’t have named death anxiety—a full-blown phobia that can induce terror—Keresophobia. Thanatos was the god of non-violent death; the Keres, his blood-thirsty sisters, were in charge of slaughter and murder and other horrifying deaths. When Thanatos whisked you off to the Underworld, it was pleasant, nothing to fear; his touch was like a whisper, soft as sleep.

Although credited for coming up with the term death anxiety, professionally speaking, he wasn’t interested in those of us often paralyzed at the prospect of nonexistence. He theorized about “the death instinct”—our back-and-forth, going-toward-death-but-not-accepting-it. We may eat lots of kale and salmon and drink red wine to try to live longer, but we’re driven by equal, if not stronger, impulses toward self-destruction.

He also said that our fear of death isn’t really a fear of death, it’s an attempt to come to terms with unresolved conflicts from childhood. It’s a fear of abandonment. Contemporary psychologists don’t say that dread and angst stem from something that happened when we were six, but many believe it has to do with unanswered psychological or physical pain.) Freud also believed that death anxiety is actually a fear of (you guessed it) castration.

To Freud, we can’t imagine death, so we can’t fear it. We live our lives unconsciously convinced that we’re immortal, seeing death as something that happens to other people. This, Freud thought, is why we praise the dead in eulogies, seeing death as a difficult task others complete, as if to say, Well done, you.

Instead of accepting our deaths, we obsess over how we may die: disease, old age, accidents, infections. The result is a shallow and empty life—particularly for Americans. (Freud hated the U.S. and all of us in it.) He wrote that death is little more than “an American flirtation, in which it is understood from the first that nothing is to happen, as contrasted with a Continental love-affair in which both partners must constantly bear its serious consequences in mind.”

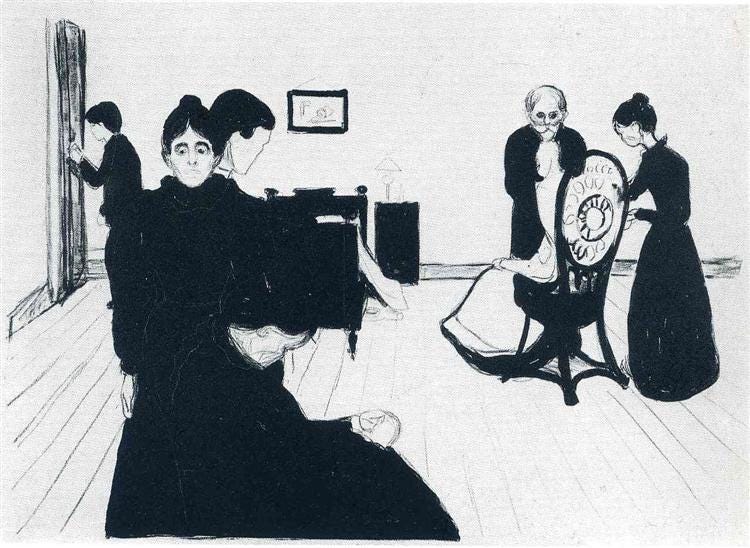

Today, thanatophobia isn’t one of the hundreds and hundreds of loosely defined mental disorders found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It’s subsumed by the catchall Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and divided into two types: a fear of death and a fear of dying. The former is a sense of dread at the prospect of being obliterated. The latter is angst about suffering or being alone as we die. Both are characterized by worry, dread, panic, fear, dizziness, heart palpitations, stomach aches, and feeling like you’re choking. Death anxiety can lead to avoidance, such as not leaving the house.

Many psychologists subscribe to Terror Management Theory (TMT). Named by professors Jeff Greenberg and Thomas Pyszczynski, TMTers study how we try to closet the reality of death, euphemistically referred to as “mortality salience.” When in the throes of mortality salience, we protect ourselves by, say, wearing sunscreen; when death has faded from our consciousness, we recklessly taunt death by, for instance, risking skin cancer with trips to the tanning salon. TMT studies have also shown that we search for meaning and try to buffer against panic by being optimistic and, as other studies found, becoming stringent in our worldviews to make ourselves seem solid, certain, not at death’s whim.

To TMTers, the way to manage death terror is through humility. Humility has long been considered a virtue and a sign of spiritual superiority marked by generosity, neighborliness, and the ability to forgive. Social psychologists consider it a personality trait characterized by a “quiet ego.” The humble aren’t neurotic about death and narcissistic about their bodies and importance. They exhibit “an accurate assessment of one’s characteristics, an ability to acknowledge limitations, and a forgetting of the self.” [Tangney, J. P. (2002). Humility. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 411– 419). New York, NY: Oxford University Press]

In five different studies, researchers found that humility acts was practically a salve against thanatophobia. Those who don’t believe they’re the center of the universe and accept mortality don’t internally scrape and claw to try to escape it. Those low in humility grow distressed when reminded that one day, they too will pass. People with “a low sense of psychological entitlement” age differently too, not defending their biases and beliefs. Just remembering times in our lives when we’ve been humble (which isn’t the same as feeling we’ve been wronged or humiliated) can lessen our death anxiety and make us feel more in control.

Freud actually established the link between humility and an acceptance of death long before TMT existed. He said that the more arrogant we are, the more amped up our thanatophobia will be.

But according to the American cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, an icon in the field of death studies, humility may not matter. If Freud is the grandfather of death anxiety, Becker is the beloved father of it. His work serves as the foundation for TMT and other types of death anxiety research. Becker theorized that we’re basically just trying to save ourselves from death by denying death, which results in selfishness, which he saw as being the root of all the evils humankind commits. Celebrities, particularly white guys, love him. Becker fans include Woody Allen, Don Delillo, Marc Maron, and Bill Clinton.

Becker believed that death terrifies all human beings—not just the thanatophobic—and we spend the majority of our lives trying to control and prevent our anxiety about it. He wasn’t interested in death per se; he wanted to know why people behave the way they do, particularly why we’re so violent. In his seminal, Pulitzer-Prize-winning book The Denial of Death, he postulates that not admitting to our own mortality causes us to become defensive and try to protect ourselves by adopting an “immortality system” (a religion, political ideology, or cultural belief), which we righteously defend in part by attacking (and possibly killing) anyone who disagrees. Hostility and violence, even war, we control death. It deludes us into believing we’re more solid than we are and might, possibly, endure. Becker worried that if humans didn’t deal with our death anxiety, we’d become eviler and eviler. Society would become more destructive.

Becker’s work has sprung “death positive” groups that want to increase our awareness and acceptance of death. But as I sit here in my apartment, with the winter wind whipping and howling outside, I prefer to keep battling my anxiety and live in total denial that I’m going to die.

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber. For $30/year, the price of a hardcover book, you help me continue to bring my writing to readers all over the world.