What’s Really Happening with the Mental Health Crisis Among Adolescents? Part 1

Answer: It’s troubling but perhaps not for the reasons you think...

A couple of weeks ago, I was in a training as part of my work as a Mental Health Peer Recovery Specialist. Peers, as we’re called, are those who’ve fully recovered from mental illness and now help others find their way to recovery. (Yes, recovery from every psychiatric diagnosis—even schizophrenia—is possible.) The facilitator stressed the importance of paying attention to the words we use (“schizo,” “loony bin,” etc.). Often, doing so makes light of those who live with psychiatric illness, e.g., I’m so OCD; I wanted to kill myself when I found out Starbucks was out of Pumpkin lattes; or He’s psychotic.

During the break, two young women, who looked to be in their early twenties, stood by the coffeemaker, talking loudly to one another. They disagreed that the terms and expressions were offensive. They felt that some people—i.e., they—have the “right” to use such terms because, like me, they’d lived with psychiatric illness.

One said, “I earned my cred.” (Translation: Street credibility.)

The other young woman agreed. “I’ve had my share of grippy sock vacations.”

A “grippy sock vacation” is an insipid colloquialism that refers to the socks given to people in hospitals, specifically psychiatric facilities and wards. (#grippysockvacation) It appears in posts as well. This young woman (whose age is unclear) filmed herself in the hospital and posted it on TikTok:

It received 17 million views.

The idea that being hospitalized and taking up a much-needed psychiatric bed is funny or entertaining is beyond unsettling.

It’s part of how adolescents (now thought to be anyone between the ages of ten and twenty-five) use social media to “talk about” mental health.

I’m not a fan of the New York Post, but this is from there.

One could argue that these posts, the two young women, and hashtags like #grippysockvacation are evidence of the lessening stigma around mental illness.

But lessening stigma entails increasing empathy and providing assistance. There was little empathy in the voices of the two young women at my training. And clever little hashtags and posts minimize the support so many people need and aren’t getting.

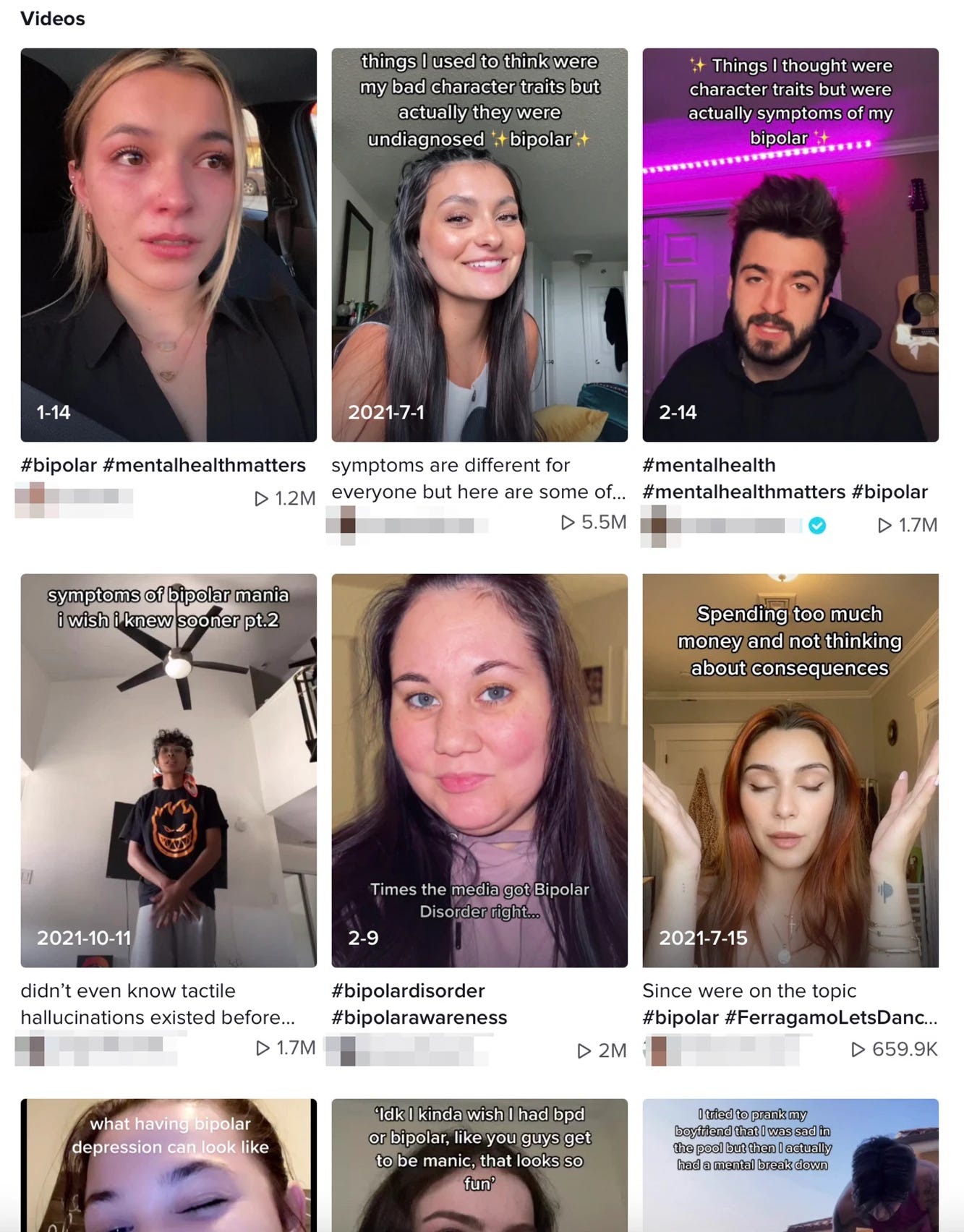

Some insist that adolescents are “finding community;” maybe, but these videos don’t provide accurate information. (See my upcoming post on misinformation on mental health videos on TikTok.) These posts profess to speak authoritatively on certain diagnoses.

But adolescents don’t know how little they know about the diagnoses they’re performing on social media. These diagnoses manifest differently in adolescents than they do in adults. More importantly, psychiatric diagnoses are, in the words of the former head of the NIMH Tom Insel, “constructs;” they’re placemarkers used by clinicians to try to get us the best care possible. (You can read more about diagnoses in my book, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses.) They were never meant for public use.

Yet use them we do. I teach at a university, and one of my students wrote an essay about having ADHD. The essay was admirable in many ways, but he wrote that ADHD became more widely diagnosed because doctors “learned more about it and could identify it more easily.” No, psychiatry’s diagnostic manual, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), changed the criteria to make diagnoses easier, and public awareness campaigns publicized the diagnosis.

I appeared at a conference with Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV task force, who’s since apologized for the “ADHD epidemic,” which he says the DSM caused. Frances wrote the diagnosis and is warning us about its flaws. If you’d like to learn more, read his mea culpa Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life.)

Sadly, my student also didn’t mention recovery from ADHD or these statistics:

Childhood ADHD has a full recovery rate of 40 to 50 percent.

One study showed that 65 percent of adolescents diagnosed with ADHD no longer met the criteria ten years later.

To be fair to my very bright student, the treatment of mental illness is a complex landscape, and misinformation is being disseminated at lightning speed.

It’s not his fault. We don’t bring recovery to people, certainly not young people. Our mental health system revolves around a biomedical and maintenance model that says diagnoses are inside us and treatment is forever.

Obviously, I’m not the target audience for young people posting on social media. The idea that a psychiatric crisis would somehow earn you social status or views or likes is incomprehensible to me. My experience of psychiatric illness was one of extreme anguish. The last thing I thought to do was grab my phone, film myself, and post it on Instagram.

We could argue that these young people are just a vocal minority. Maybe, but it’s an influential minority: millions of views isn’t unheard of.

This strange, opportunistic enthusiasm for mental and emotional distress extends beyond social media. New York Times reporter Christina Caron examines how teens are self-diagnosing and requesting specific diagnoses from mental health professionals, largely based on what they’ve seen on social media. (Teens are more likely to search social media platforms like TikTok than Google to get information. I’ll give you a moment to let that sink in: they search TikTok, not Google.)

Public awareness campaigns and social media have made us very, very aware of diagnoses and what psychic suffering is supposed to look like. If you want a brilliant book on this topic, read psychologist Lucy Foulkes’s Losing Our Minds: The Challenge of Defining Mental Illness. (You can also read my op-ed on how mental health awareness campaigns have backfired here.)

I don’t question whether the mental health crisis among adolescents is real. According to The White House, the U.S. Surgeon General, and media outlets like the Washington Post, it is. The sheer number of children and teens in distress supports it. Then there’s the shortage of clinicians, the lack of access to care, and the number of providers who don’t accept insurance. Between 2007 and 2018, suicide rates in young adults, ages ten to twenty-four, doubled. The crisis isn’t just the result of COVID-19 and doesn’t have an easy answer; other stressors include school shootings, racial injustice, climate change, and social media, to name a few, and has been building since at least 2016.

And, of course, young people should get help. Ultimately, we want to support youth. But a little time spent on social media makes one disconcerted about other factors that may be playing a role and which aren’t being taken into account.

Read part 2 of this post here.

For more on what we should be talking about, i.e., mental health recovery, read Cured: The Memoir.

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber for $30/year, the equivalent price of a hardcover book.

When my mom was a teenager she told everyone she was having a nervous breakdown so she could leave school and take time off. It was only years later that she realized she had in fact been experiencing a break down and the desire to tell everyone that was a sign of a real problem. That’s what I thought of when I read your post. Every child or teen should be getting help right now. Ever single one. Especially those who are exposing themselves in ways we might find incomprehensible. It’s not a trend. It’s a sign of something much deeper.

I'm glad your Note linked to these two articles, Sarah. They broadened my understanding of adolescents and mental health.