What’s the Most Important Thing You Can Do for Your Mental Health?

Answer: I’m not sure, but here’s what it was for me

I sit here at my desk with my cat at my feet. It’s sunny outside. For two months, Chicago has had perfect weather—blue skies, temperatures in the high seventies and low eighties—and I’ve been inside.

It was worth it; I just finished the sequel to Pathological, which is still untitled. In it, I tell of my full recovery from twenty-five years of serious mental illness and what I did to heal. Spoiler: I had to do a lot. It was years of physical, mental, and emotional boot camp. But I made it.

It’s a much longer story, but the most critical thing I did (though there wasn’t one) was to learn what emotions are and how to process them. Little did I know this would be a herculean task. Emotions are, for the most part, a mystery, even to those whose sole occupation is to know what they are.

First, I learned that there is currently a revolution going on among emotion theorists. The battle rages between the classicalists and the constructivists. The classical view of emotion was likely taught to you in kindergarten and is continually reinforced in popular culture, pop psychology, and self-help books. It states that emotions are distinct and universal: happiness and sadness register in the body the same way for you as for me. A facial expression like a smile equates to a single emotion like happiness. We can know what other people are feeling by “reading” their faces. Emotions are triggered by the world around us, seemingly beyond our control: a life event (e.g., get a kitten) activates a distinct, absolute version of an emotion (e.g., joy). An emotion is experienced the same way in every circumstance. Our brains are hardwired for emotions: one neuron equals happiness, another sadness. Emotions are continually in conflict with rational thought.

This classical view dates to at least the 1850s; it became the basis of neuroscience during the 1990s, a.k.a. “the Decade of the Brain.” The 1990s was an era of astonishingly expensive research studies, most trying to prove that emotions—and the mental health diagnoses associated with them—have neurological fingerprints. The neurobiology of emotion tended to examine so-called negative emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety) in terms of brain processes, neural pathways, synaptic transmission, and neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin.

Enter: the revolution.

The constructivist view argues that the classical view (which also serves as the basis of our current thinking about mental illness and determines the treatments we use) is wrong. It states that emotions are socially constructed and not at all universal. Cultural norms and our preconceived notions about what emotion should be dictate much of the classical mapping of emotions: sadness equals crying, happiness translates as laughing. Sadness to an American isn’t the same as sadness to a Nigerian. Facial expressions don’t reveal emotion, and we can’t “tell” what other people are feeling.

Constructivists say that emotions manifest in the body differently in each person in different ways according to the context. In a 2018 lecture at New Zealand’s University of Waikato, neuropsychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett explained, “[A]n ache in your stomach can be anxiety if you’re waiting for a test result. It can be hunger if it’s dinner time. It can be longing if you miss someone close to you. And it can be a gut feeling that someone is guilty if you’re a judge or juror in a trial.” (Feldman is an icon in the field, practically single-handedly shaking up the world of emotion theory.)

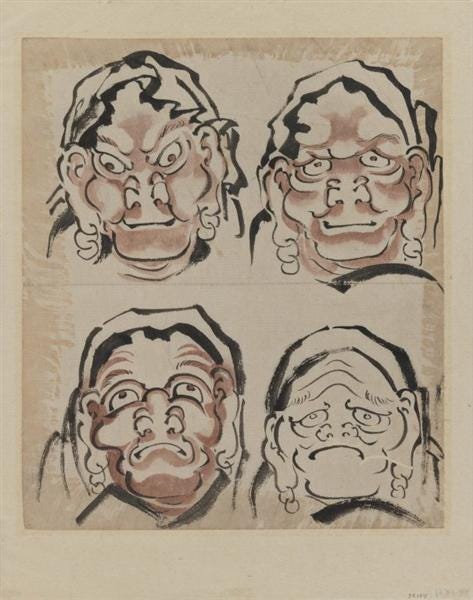

We also experience “incongruous emotions.” We smile and laugh when we’re happy but also when we’re scared, threatened, or overwhelmed by sadness. In a threatening situation, we might smile to appease the source of the threat or to pacify ourselves that we aren’t really in danger. While experiencing grief, we might smile and laugh to try to combat an overpowering negative emotion.

To the constructivists, emotions aren’t reactive, and there are no dedicated circuits in the brain for particular emotions. The amygdala isn’t the fear center; it plays many roles, as do other parts of the brain. Emotions are part of the brain’s efforts to keep you alive and are integrated into its attempts to predict what will happen next.

The constructivist view blows open the whole emoji-smiley-face-equals happiness concept of emotions. It’s more complex than what’s here, and it gets intellectually noodle-y pretty fast, but it changed my view of myself, my emotional life, and the world. I thought of anxiety, depression, joy, loneliness, etc. as entities, but they’re just labels we put on our responses to experiences. They’re approximations, primarily driven by the brain’s desire to keep us alive.

This may be disappointing, especially if you’re trying to better understand emotions and, say, recently purchased Brene Brown’s Atlas of the Heart. In it, she tries to draw us a (you guessed it) map of our emotions. It means well and is very useful until you discover, as I did, that the classical view is reductionist and likely totally off-base.

If you want to dip into the harsh reality of emotion theory, read Lisa Feldman Barrett’s How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. It’s a deep look at the science of emotion and not for the faint of heart. Noodle-y. But also worth it.

Support independent journalism. Readers like you make my work possible. Get the annual discounted subscription—about the equivalent of purchasing one hardcover book.

Buy Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins) here:

*