Who Invented Emotions?

Who Invented Emotions?

The answer? It’s complicated.

No one can define what exactly an emotion is. On the most basic level, an emotion is a sensation or a series of vibrations in the body: a fluttering heart, sweaty hands, a stomachache, weak knees; a pulsing sensation in your head, a weight on your chest, the tightening of your shoulders and neck, a rush of warmth to your face. The American Psychological Association (APA) describes it as “a complex reaction pattern involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements.” Merriam-Webster defines it as “a conscious mental reaction…subjectively experienced as strong feeling…typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body.” Emotions aren’t discrete categories. The bodily sensations we attach to one emotion can apply to another. A churning stomach, shakiness, and a rapid heartbeat could indicate anger but also fear.

Emotions occur for different reasons and have numerous effects. Some emotions are passive, others active. We’re consciously aware of some while others seem to pass through us without us being able to process them. Some manifest externally (a smile, crying) while others are invisible to those around us. We can spend days, weeks, months, or years experiencing some (depression, anxiety) whereas others pass through us almost instantaneously.

I spent thirty years at the mercy of my emotions, not being able to even name them. The sweaty palms and rushes of tears and pits in my stomach seemed to come and cripple me and then go without reason. Over that time, I was diagnosed with six different mental illnesses: anorexia, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and bipolar disorder. None of these labels made identifying and managing my emotions any easier. One day after working out at the gym, an existential panic descended on me. It wasn’t just that my heart was beating fast and I was dizzy and disoriented; I was certain that I was about to die. Was that fear? Terror? Horror? Given that I was not in fact dying, did my thoughts create the feelings in my body or did my body make me think that I was dying? Was I finally going crazy, i.e., losing my faculties for good?

The Physiology of Emotions

The physiology of emotions has been a matter of much debate. Which emotions result in which movements, postures, and gestures? Does delight necessarily generate laughter? Not always. We experience “incongruous emotions.” We smile and laugh when we’re scared or threatened or overwhelmed by sadness. We may do so to appease the source of the threat. Or to pacify ourselves that we aren’t really in danger. Or to regulate an overpowering negative emotion (grief) with a positive one (laughter).

Many attempts have been made to associate emotions with parts of the body.

These studies aren’t objective—or definitive. The results aren’t based on MRIs or body scans; they’re computerized renderings of where in the body participants reported stimulation in response to words, stories, movies, and facial expressions. Of course, much of the mapping of emotions is dictated by cultural norms and our preconceived notions about what emotion should be: sadness is felt in the head (tears) and the chest (heaving), happiness equates to smiles and feeling good all over.

Whole disciplines are devoted to trying to parse emotions: affective science, emotion research, emotional psychology. Other fields study it: psychiatry, nursing, psychology, sociology, anthropology, economics, communication studies, criminal law, political science, PR and advertising, philosophy. And still, emotions remain illusory.

If you start to catalog the various theories, more questions ensue. What are emotions versus sensations versus feelings versus moods? Are emotions judgments? Appraisals? Do they motivate us to act? Are they little more than primitive responses to our environment? Are they genetic and the result of our neurobiology?

Primary or Secondary

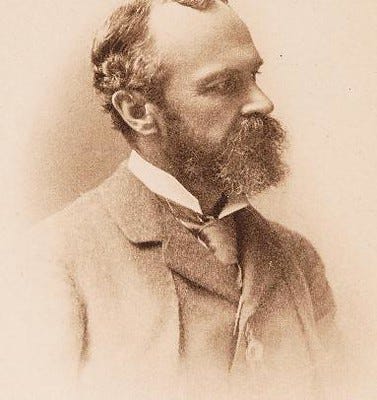

Theorists have been arguing for at least two centuries about which emotions are primary and which secondary. The nineteenth-century philosopher and psychologist (and brother to Henry) William James said there are four basic emotions: fear, grief, love, and rage.

The twentieth-century psychologist Paul Ekman proposed seven: fear, anger, joy, sadness, contempt, disgust, and surprise. The twentieth-century psychologist Robert Plutchik gave us the famous “Wheel of Emotion,” which singles out eight emotions that exist in opposition: joy/sadness, anger/fear, trust/disgust, and surprise/anticipation. Other binaries have been suggested: love v. hate, joy v. sadness, trust v. disgust, and anticipation v. surprise. Twenty-first-century researchers have since brought the number back down to four: happy, sad, afraid/surprised, angry/disgusted.

This way of thinking assumes that emotions are a psychological category. Before the nineteenth century, bodily sensations were considered transcendental, utilitarian, dangerous, or virtuous. Chinese philosophers called affective states qing, the essence of one’s inner being and the motivator of one’s outer commitment to society. The Stoics saw them as unruly, disruptive passions that had to be controlled by the rational mind. Medieval theologians separated them into positive and negative and interpreted them as indications of a person’s morality. Eighteenth-century theorists continued to divide them into positive and negative: vain and violent passions/appetites versus benevolent and kind affections and sentiments.

The Inventor(s)

You could say, as emotions scholar Thomas Dixon does, that one man invented emotions as a psychological category: the nineteenth-century Scottish Professor of philosophy Thomas Brown. (Not to be confused with Sir Thomas Browne, the physician who authored Religio Medici.) Although others played a part, notably philosopher David Hume and theologian and minister Thomas Chalmers, Brown took the word emotion (a translation of the French émotion, meaning a disturbance of one’s physical state) and used it as an umbrella term to indicate all passions, appetites, affections, and sentiments. Brown died young, at forty-two, in 1820. Best known for his Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind, he was devoted to his work, never marrying or having children.

Others followed, contributing to our understanding of the category called emotion. The nineteenth-century ushered in an emphasis on the face as the loci for emotion. In 1824, the Scottish surgeon and neurologist Charles Bell (Bell’s palsy is named for him) published Essays on The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression, in which he examined the expressive role of facial muscles. In 1862, the French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne used “electrotherapy” to treat muscular disorders. In the process, he tried to connect facial expressions to their corresponding emotions, publishing his results in Mécanisme de la Physionomie Humaine.

In the 1872 illustrated The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin argued that certain universal emotions exist in humans and even animals: anger, fear, surprise, disgust, happiness, and sadness.

But they serve no evolutionary purpose. They don’t, for instance, help us communicate (Is she smiling because she’s happy, fearful, anxious?) or survive (What good is an appeasing smile when running from a lion?).

The 1880s and 1890s brought theoretical arguments as to how, when, and why emotions occur. The James-Lange theory, as it’s known (William James and Charles Lange actually came up with separate theories that have since been conflated), states that emotions come as a result of bodily sensations. (Hence, the smile-and-you’ll-be-happy self-help adage.) Harvard physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon and his doctoral student Phillip Bard came up with the Cannon-Bard theory, which claimed that we experience the stimulating event or situation and the corresponding emotional response simultaneously.

Flash forward to the mid-twentieth century, when the study of emotion had its heyday. The 1960s brought psychologists Richard Lazarus, Stanley Schachter, and Jerome Singer, who focused on the relationship between thought and emotion. Paul Ekman argued that emotions aren’t universal but dependent on culture.

The 1990s was, according to President George Bush Senior, “the Decade of the Brain.” It was a time of very expensive research studies, many trying to prove that emotions and the mental health diagnoses associated with them are located entirely in the brain. The neurobiology of emotion tended to examine so-called negative emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety), speaking of them in terms of brain processes, neural pathways, synaptic transmission, and neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin. Despite lots of pretty MRI scans, none of what was theorized was proven. Emotions were and are still conceptual.

The Male Gaze

Much of our understanding of emotions comes from men. One of the few exceptions is Magda B. Arnold.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that she was a woman, Arnold was undervalued and unappreciated—and still is. In the 1960s, she was the first to propose a complete theory of emotion.

Whereas others focused narrowly on an aspect or two, Arnold examined the emotional experience from start to finish. First, a life event occurs. Then we have a thought about it. We “appraise” it, to use Arnold’s term. Then an emotion is elicited by the thought, and we take action in response to the emotion. The emotional experience includes a stimulus (event/situation), a judgment about the stimulus (good or bad?), an emotion that arises because of the judgment (like or dislike?), and an action taken as a result (approach or withdraw?):

In some ways, who invented emotions depends on what you think emotions are and whose theory with which you agree. I’m partial to Arnold, the outlier in the field. That day at the gym, I thought I was going to die, I didn’t like it, and I considered calling 911 or telling the young woman at the front desk who’d cheerily greeted me that something was very, very wrong with me.

But what was the situation, the life event? Nothing had happened. There was no stimulus.

This is how I define mental illness: mental, emotional, and behavioral responses that don’t correspond to reality and render the person acutely dysfunctional. In this, I had or have a mental illness. (I say had or have because we have no scientific proof that mental illness is chronic, despite what some clinicians and the internet may tell us.) I was unable to live independently for five years.

The Reptile Self

One discipline of the study of emotions has helped me understand myself—my emotions, mind, and body—a little better: evolutionary psychology/psychiatry. My exposure to that branch of psychiatry, which started in the 1990s, began with a book: physician and scientist Randolph Nesse’s Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry.

After thirty years, I started to get well. (This is a much longer story, which I tell in my memoir, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses.) One of the most beautiful consequences of my hard-won mental health was that my father and I started having lunch together every Sunday. It quickly became one of the highlights of my week. I may have suggested we read Nesse’s book, but most likely my father did. It was one of The Economist’s “Books of the Year,” and my father is devoted to The Economist.

Nesse offers a paradigm I’d never considered. Maybe emotions like anxiety and depression aren’t pathological; maybe they date back to primitive humankind and for some reason haven’t been eliminated by natural selection. Anxiety (even edginess) may have helped primitive humans stay alert and run from lions on the veldt. Unlike Darwin, Nesse posits that depression might be a reasonable—even evolutionarily beneficial—way of responding to stress. The emotion of depression (a slowing, a weight) could be the body’s response to extended periods of the emotion of anxiety (rushes of adrenaline, edginess, the sense of splintering and then cracking).

I like the idea that my often extreme emotions (yes, still) are the result of the fact that the mind is perfectly designed to respond to danger. It’s programmed to protect us and conserve energy and that’s it. Humans are designed to fight, love/procreate, belong to a clan, and escape predators. The cortex part of the brain may appraise, as Arnold put it, but it’s driven by the primitive parts. Deep down, we’re just reptiles trying to survive.

Our cerebral structure would be fine except that many people live comparatively free of threat. Extreme emotions, responses, and thoughts are natural but no longer useful. I like to think that exceptionally anxious people like myself are the ones you would have wanted in your clan. We’re always on the lookout for a lion, even when we’re just answering emails.

This is a simplistic summary of evolutionary psychiatry, and evolutionary psychiatry has its problems and its share of critics. But it and Arnold’s view of how thoughts create our emotions help me make sense of myself and the world.

Support independent journalism. Readers like you make my work possible. Get the annual discounted subscription—about the equivalent of purchasing one hardcover book.

Buy Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins) here:

Oh I love this!