If you think you’ve never heard of neuromythology, you actually already know what it is and if you’re like me, probably succumb to it on a regular basis.

A neuromyth is a false, common misconception about neuroscience. It’s our incorrect assumptions about what the brain does and doesn’t do.

Neuromythology is particularly prevalent in mental health research and treatment.

Something is comforting about the idea that our mental and emotional lives—ethereal and often indescribable—are somehow solid. We like to believe that our depressions and anxiety and compulsions are caused by brain phenomena: chemical imbalances, misfiring neurons, depleted grey matter. It’s all very reasonable. We want our disordered, confused, and troubling thoughts, feelings, and emotions to have a simple explanation.

And something about all those pretty pictures of brain scans and men (usually men) in white coats telling us that our brains are responsible for this imbalance or that misfiring when we have no proof is irresistible.

Who’s to blame?

Psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental health professionals aren’t totally to blame though they’re disseminating psycho-neurmythology at an astounding rate.

It may seem like I’m being very antipsychiatry to point out the flaws in and dangers of believing the biomedical model of mental disorders, psychiatry’s claim that mental disorders come from the brain, but I’m just pointing out some facts:

Biopsychiatrists pushed the idea that mental disorders are “brain diseases” based on zero conclusive evidence.

The majority of psychiatrists perpetuated this misinformation (not to mention primary care physicians, psychologists, and social workers) to their patients, their families, the press, and just about everyone else.

They campaigned for neurological explanations at the expense of other potential factors, such as environment, a patient’s personality, and social and economic injustices.

The rise of what’s referred to as the second wave of biopsychiatry in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s had everything to do with why we think that our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are dictated by the wiring in our brains. This created an unethical relationship with Big Pharma, which pounced on the biological explanation to sell psychotropic drugs.

But—and I mean this—psychiatry’s intentions were relatively good. Insofar as I’ve been able to discern, biopsychiatrists and researchers wanted tangible answers to explain our mental and emotional suffering—to a dangerous degree. Like many of us, they wanted those answers to be simple, seemingly definitive, and convincing.

Psychiatry wasn’t alone; others played a role.

The media helped keep the American public believing in psychiatry’s biomedical model as did the way certain mental health diagnoses have been embraced by popular culture as “cool.” Unsurprisingly, another major player has been pharmaceutical companies, which have benefited greatly from our devotions to neurological explanations for aspects of the human experience (depression, anxiety, paranoia, obsessiveness, distractibility), which are subjective and indefinable.

Researchers played a role. All those colorful brain scans seem to prove that schizophrenia must be caused by all sorts of neuronal things like, maybe, variations in grey matter, even though such variations can occur as a result of many factors, including prolonged insomnia, concussion, and smoking.

The computerized renderings of uncommunicative neurotransmitters

![NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet], National Institutes of Health (US); Biological Sciences Curriculum Study, Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US); 2007. NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet], National Institutes of Health (US); Biological Sciences Curriculum Study, Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US); 2007.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!SBLl!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdb31a041-c047-4b37-9697-360c7e9d04d8_364x746.jpeg)

seemed to offer scientific accounts of what’s happening when we have no interest in life, feel an almost intolerable heaviness in our bodies, and withdraw from others (i.e., depression).

The Image Isn’t Proof

The problem is that brain scans and computerized renderings aren’t as definite as they may appear—not just in psychiatry but in all areas of medicine. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was introduced in the 1990s during President George H. W. Bush’s Decade of the Brain. The mandate was an inter-organizational campaign that included the Library of Congress and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This meant that there was a lot of money spent on neurological studies—not to mention media attention—even if the study didn’t prove anything.

The 2010s should have brought about a tempering our enthusiasm for neurological studies based on brain imaging. Studies found that research that relied on fMRI produced false-positive rates of up to 70 percent. (A typical false-positive rate is 5 percent.) (Somewhat humorously, the limitations of studies that relied on fMRI data arose when neuroscientists stuck a dead salmon in an fMRI machine and its brain “lit up,” just like all those live human brains did.)

Other reports showed how bias affected neurological studies and the number of such studies that couldn’t be replicated.

Yet we like and want to believe that our human experience can be explained through a neuroscientific lens. Research has shown that it may not be the colorful photos of our amygdalae or the scientific jargon that often goes along with them. We trust neurological explanations of our mental health or mental illnesses because they’re easy.

Mental Health Diagnoses Aren’t Scientifically Proven to Begin With

The particular problem with believing the neurological and biological claims to mental health diagnoses is that the mental health diagnoses are invalid and largely unreliable. Our diagnoses come from a book: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—which is authored primarily by members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the organization that publishes and profits from the DSM. The DSM isn’t a scientific manual. Except for dementia and rare chromosomal disorders, all our mental health diagnoses are invented based not on scientific discoveries but the opinions and theories of those authors.

The neuromythology surrounding the DSM is pervasive. Many people believe that DSM diagnoses like depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, etc. are hereditary, permanent, and biological, no DSM diagnosis (again, except dementia and rare chromosomal disorders) has been shown to be genetic or chronic or caused by biology or a chemical imbalance. No biological marker—no blood test, x-ray, or brain scan—can show that DSM disorders exist outside of a patient’s self-reported symptoms and a clinician’s opinion. They’re largely unreliable, meaning two clinicians assessing the same patient at the same time won’t give the same diagnosis. Clinicians using the DSM’s criteria as their guide have about a fifty-fifty chance of coming to the same conclusion—the same as flipping a coin.

Psychiatry wanted it this way; the goal was to make psychiatry a respected, scientific field of medicine. The biomedical model promised to prove that psychiatry was scientific—of the brain—not ideological—of the mind. It was referred to as “the psychopharmacology revolution.” It led a lot of people to believe they had (and have) mental disorders when all they have is an idea about a theory based on an opinion. It also convinced a lot of people to take psychotropic medications, which were equally theoretical in terms of their efficacy.

The campaign for the biomedical model of mental disorders started in 1980 when the third edition of the DSM (DSM-III) was published. It gained traction throughout the Decade of the Brain and the early 2000s. It wasn’t until the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5), that people started to question it. Why, after thirty years, had psychiatry failed to prove the objective existence of all but two categories of mental disorders? (By that point, there were 541 diagnostic categories in the DSM.)

A favorite claim was that neuroimaging scans (fMRI) could show that diagnoses like depression and schizophrenia exist in the brain. Most often, it’s said that they can show which areas of the brain are “involved” or “light up” in people with mental health diagnoses. The other click-bait favorite is the declaration that fMRIs detect abnormalities in different parts of the brain in patients. Another is that such images can predict the likelihood of a person developing a diagnosis. In reality, fMRI technology can only rule out if a person’s symptoms are caused by an organic illness (brain tumor, Alzheimer’s) and that’s it.

The Mind-Body Problem

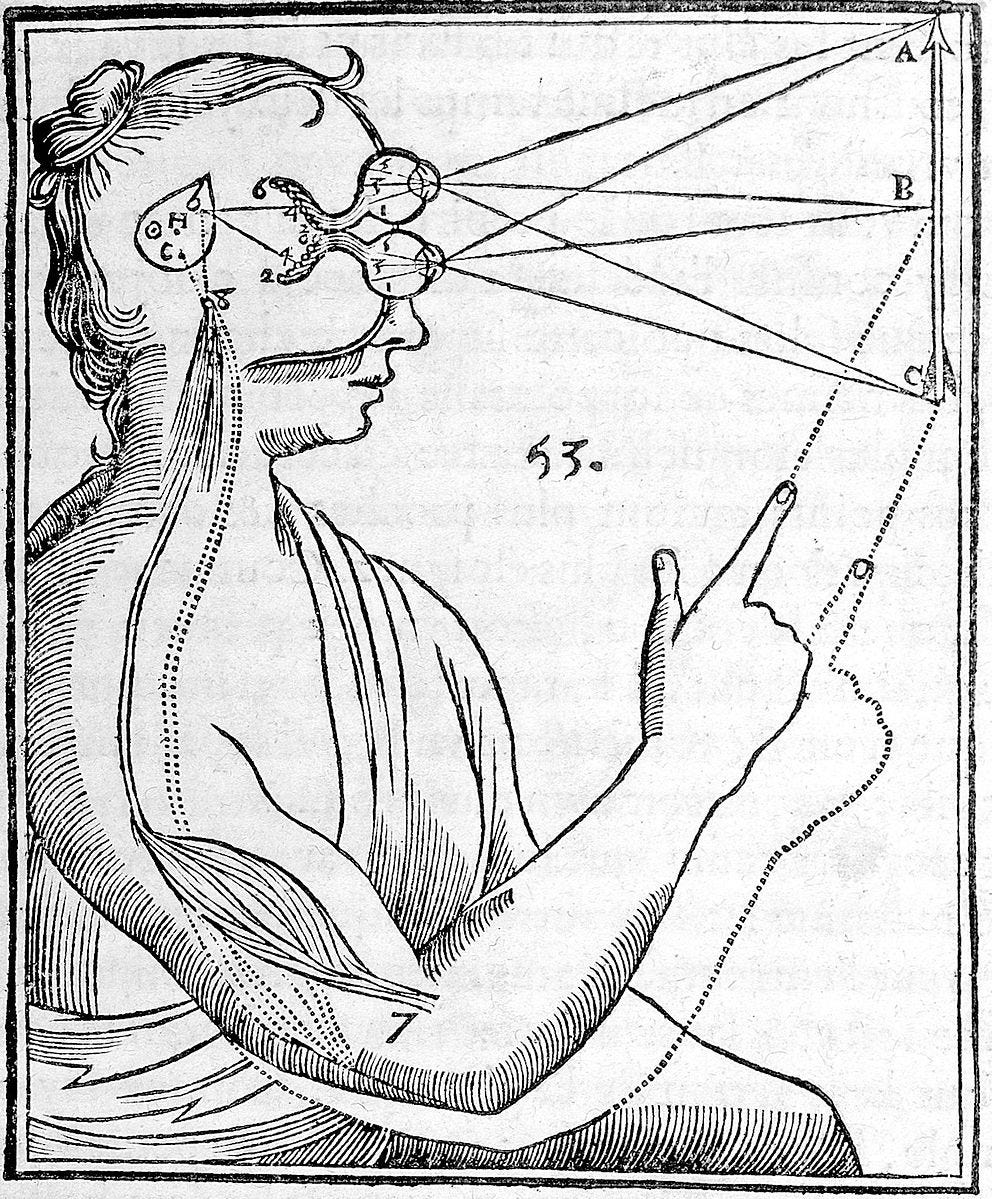

All this leads to a single fundamental question: Do our mental and emotional lives take place in the mind or the brain? The answer to this depends on whether you believe the mind is separate from the brain (which depends on whether you think we have a mind at all). The mind-body problem is too complex and vast to cover here but essentially it asks what the relationship is between the physical (brain) and the mental (the metaphysical mind).

Psychiatry’s push toward the biomedical model actually goes against the very title of its medical manual: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The definition of mental is “of or relating to the mind.” But the idea that our existence—particularly the troubling, destructive, and even criminal aspects—is purely physical and therefore easy to grasp was too tempting to resist despite evidence to the contrary.

Context matters

To defend psychiatry, our fervent and unfounded belief in the neuromythology of mental disorders didn’t come only from psychiatrists and mental health professionals. Primary care physicians are responsible for nearly 80 percent of all psychiatric diagnoses and prescriptions. Primary care physicians have little psychiatric training—about sixteen weeks total and then only in in-patient settings with the most severe cases, not during a fifteen-minute annual exam before which the patient filled out a very leading questionnaire asking if he/she/they have been depressed lately.

In theory, psychiatry has endorsed a bio-psycho-social model of mental illness for many years, but mental health diagnoses and the neuromythology surrounding them are a work of culture. Mental health diagnoses are memes; some are considered “cool.” We self-diagnose on social media.

One of the most passionate arguments in favor of perpetuating the biomedical model of mental disorders is that it somehow reduces stigma. The idea is that saying that a disorder is biological, hereditary, and chronic supposedly prevents a person from feeling like he/she is or they are responsible and that their complaints aren’t valid. It’s a nice idea, but it’s not true. One study showed that attaching a supposed biological cause to a diagnosis actually produced shame, pessimism, negativity, and hopelessness about the future The problem is that’s not the case; it’s been shown to increase stigma. One study found that attaching a supposed biological cause to a diagnosis increased self-stigma too, provoking feelings of shame, pessimism, negativity, and hopelessness about the future.

Neuromythology exists in other areas of medicine, but psychiatry is the only field that has nothing to offer but speculation, sometimes presented in the form of colorful pictures and images. It comes down to the question of brain or mind—which or both?

Thank you! Readers like you make my work possible.

The best way to show your support is to purchase or gift a copy of my bestselling memoir Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses. It was hailed in The New York Times for its “spikey intelligence.”

Pathological was an Apple Best Books pick and Kirkus starred review. Bestselling author Johann Hari called it “a crucial and necessary book.”

My psychiatrist said it should be required reading for all medical residents.

I would add any human who’s been touched by mental illness.

The more we know, the more powerful we are.

I’ve had direct experience of conflicting and misapplied diagnoses. Many thanks for this clear-eyed report.

🙏. Any -ism is reductionism. That unfortunately is still the biggest problem in mental health. We reduce it to symptoms, to cause effect models, to brain matter. It would already help to just look how other cultures look at mental health from a more systemic perspective. TCM for instance does not even treat symptoms but systems. And our mental and emotional life is just part of that bigger picture.

But we have to tread carefully to not demonize it all. I for instance think that PTSD diagnosis was a blessing for many to finally understand what was going on with them and in them, e.g. all those broken soldiers coming home. Unfortunately it has been also too widely used and now every adverse live event is seen as traumatic which is just not good evidence based science in the first place. And the treatment itself has become a victim of the biomedical model ignoring the whole existential dimension of traumatic experience.

I think our MH system suffers a kind of “epistemological despair,” as I call it.

It only believes what it sees which are data points or neurons firing. But it does not know how to interpret it in the bigger picture. Nor how to empower patients to become their own best experts as you did! That would require to integrate the Socratic “understand thyself” into the picture.

Well, you got me going here, Sarah!