Why Is Anxiety a Problem?

Answer: It doesn’t have to be.

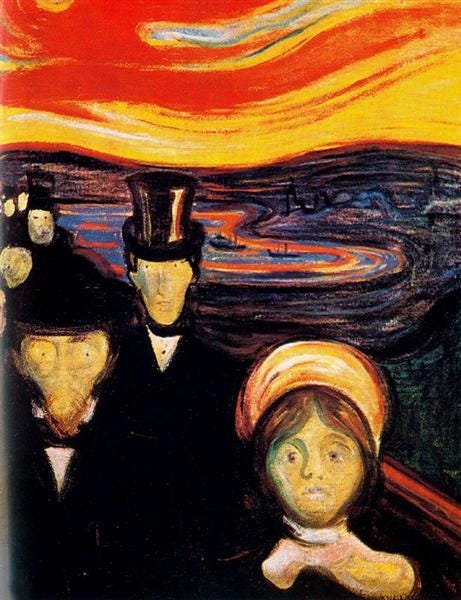

Although we seek to avoid anxiety, historically, it’s been seen as a normal, human, even beneficial emotion. To the existentialists, it was an important part of our humanness. The philosopher Soren Kierkegaard thought it was crucial for success in life: “Whoever is educated by anxiety is educated by possibility.” Studies have since shown this to be true. Anxiety actually makes us perform better. It motivates us.

Anxiety occurs in the body. The American Psychological Association defines anxiety as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like increased blood pressure.” The word anxiety word stems from the Latin verb angor, meaning to constrict. Some languages equate it with anguish while others see the two—anxiety, anguish—as different: anxiety is a mental state like worry whereas anguish is a physical feeling that results from such worry. Although anxious thoughts and emotions create a physical response in the body, there’s no definitive evidence that the causes of anxiety disorders are biological.

For decades, scientists and researchers have been trying to figure out where and how anxiety is produced in the brain. At first, it seemed like anxiety lived in the amygdala. The amygdala is a mass about the size of an almond in the temporal lobe, just behind your ear. But we now know it’s more complex than that. The amygdala alone isn’t responsible. Anxiety arises as a result of the constant conversation going on among different areas of the brain. Neurotransmitters are involved too. Just how it all works, we’re still not sure.

Much of our understanding of anxiety as a bad thing comes from Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. He basically invented pathological anxiety and made it the centerpiece of mental disorders. For Freud (and the Ancient Greeks), anxiety was different from fear in that anxiety was about expecting and dreading danger that may or may not come whereas fear was in response to an actual threat.

Freud is just one part of the short history of how we came to think of anxiety as a mental illness. In antiquity, it was thought of as an illness by some or an annoyance by others. The Epicureans and Stoics offered a simple cure for it: stop regretting the past and fearing the future. In the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries it was seen as a symptom of other mental conditions. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was the core feature of “nervous disorder” (neurasthenia), manic-depressive illness, and Freudian neurosis. In the first editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), anxiety, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive thoughts and responses were considered neurotic conditions. The DSM-III defined two types of anxiety according to anxiety’s etymological roots: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), which cognitively manifests as worry, and panic disorder (PD), which produces physical responses.

Over the various editions of the DSM, it’s become easier to diagnose and be told you are mentally ill rather than human. The DSM-III stipulated that you can’t have regular old vanilla worry; it had to be “unrealistic,” which meant that worrying about the loss of one’s job after losing a big deal or making major errors on a year-end report, for instance, wouldn’t qualify for a diagnosis. It’s not unrealistic to think that might lead you to be fired. The DSM-IV loosened the criteria by removing the term “unrealistic,” which meant any and all worry was fair game. As diagnostic criteria have loosened, there occurred a correlative increase in the number of people diagnosed. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) went up by almost 20 percent. The DSM-5 has also helped make it the most common mental health diagnosis. The DSM-5 decreased the amount of time a person had to experience anxiety to qualify for a diagnosis (from six months to three months).

Easy diagnoses can lead to overdiagnosis, which is at least part of the reason that anxiety disorders are the most common mental health diagnosis today. Which is why Americans have such a negative, contentious relationship with anxiety. The multi-million-dollar “anxiety product economy” is proof of our desire to rid ourselves of an emotion once thought valuable.

What if we allowed anxiety (and depression and racing thoughts and distractibility and compulsive behaviors and hyperactivity) to be there? What if when they came, we didn’t assume anything had gone wrong?

What is recovery from mental illness?

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines recovery as “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.”

To learn more about recovery, go here.

Read more about my recovery from mental illness in the exclusive publication of my new memoir Cured. You can read it for free through 2023: