Note: This installment describes suicidality. If you’re having thoughts of suicide, speaking to someone can help. You aren’t alone. Call or text 988. If you don’t feel you’re a danger to yourself, call or text one of the many warmlines available.

» For tips on how to develop your or your loved one’s or friend’s safety plan, go here:

Mayo Clinic, Suicide Crisis: How to develop your safety plan

Samaritans, Creating a ‘safety plan’

My friend Lisa picks me up in her Subaru, and we drive to the suburbs. The idea is to get some things for my claustrophobic studio apartment to make it “homier.” Interior decoration appeals to me about as much as breaking a bone: painful at first and then just tedious.

But I want to be “normal.” After twenty-five years in the mental health system—an eternity, it seems now—my new psychiatrist has told me that recovery from psychiatric disorders is, in fact, possible, a secret none of the many clinicians I saw ever divulged. According to them, my diagnoses (I received six, one after another, trying to give a name to my mental and emotional pain) were lifelong. The best I could do was manage my symptoms. Now, I’m trying to heal inside a fantasy of what’s “normal” and what’s not.

We head west and eventually merge onto the highway. We’ve been friends for twenty years, ever since we both waited tables at the same restaurant. We fall in and out of touch. During one of my deepest depressions, I lived with her for about a month.

Lisa tells me her jewelry business is struggling. She’s dyed her dark hair blonde, which makes her perfect porcelain skin look even more flawless.

During a lull, I look out the window. The landscape seems to blur though Lisa isn’t driving that fast. Pressure builds in my chest. The pressure flutters, then tingles, then pulses.

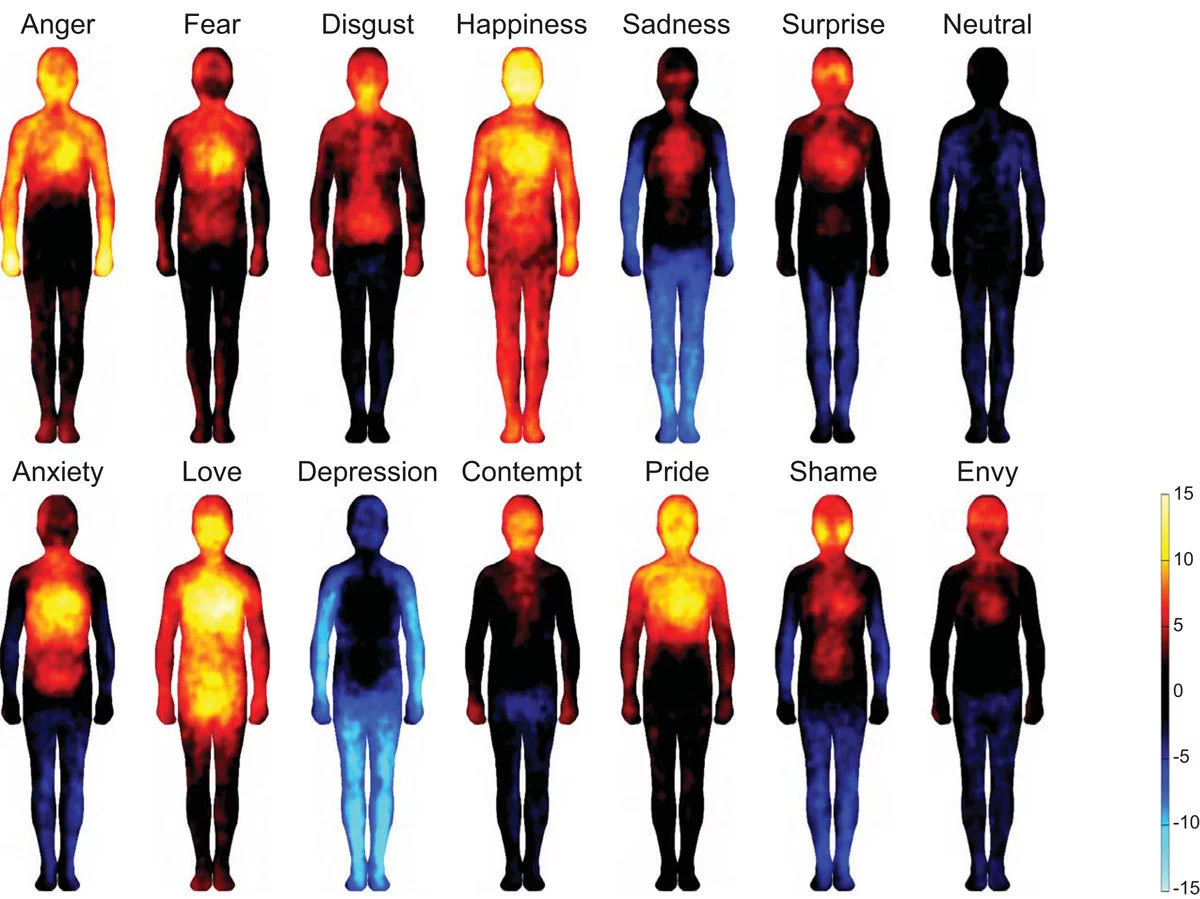

I couldn’t name it then, but that’s how anxiety and fear manifest in my body. The American Psychological Association (APA) describes an emotion as “a complex reaction pattern involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements.” Merriam-Webster defines it as “a conscious mental reaction…subjectively experienced as strong feeling…typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body.” Some emotion theorists say we can physically map our emotions:

At the time, like many people, I didn’t even know that an emotion is a sensation or a series of vibrations in the body: a fluttering heart, sweaty hands, a stomachache, weak knees, a pulsing sensation in your head, heavy limbs, the tightening of your shoulders and neck, a rush of warmth to your face.

She asks how I’m doing. It’s as if the car veers too close to the traffic barrier. I try to sound peppy and say I’m fine, hearing the waver in my voice.

I deflect the conversation back to Lisa, who tells me about the man she’s dating. The pulsing in my chest increases. My cheeks seem to go numb.

Between the city limits and O’Hare, there are plenty of opportunities to ask Lisa to turn the car around. A couple of years ago, during one of the times we reconnected by phone, I told her I was bipolar. Her response was one of deep sympathy. But I don’t say anything and then it seems too late.

In IKEA, amidst seemingly endless objects—lamps and kitchen towels the store promises will give my harrowingly small apartment a “calm, peaceful vibe”—it starts. Passing through one of several demo kitchens, I feel my cheeks go numb. Pain shoots down my arm. A heart attack. I must be having a heart attack.

If I ignore it, maybe it will go away. Mentally healthy people shop at IKEA without having panic attacks, or so I think, putting a meaningless circular blue throw pillow in my cart, then a random drawer unit designed to permanently organize toiletries, then a cutting board I don’t need and a white decorative bowl I never wanted.

We’re headed to the checkout when she says she’s hungry. “Let’s stop at the cafeteria.” She loves IKEA’s mashed potatoes and gravy.

My mind races: I’m dying. I must be dying. I have to get out of here.

I smile. She orders mashed potatoes with gravy. At the soda fountain, she fills an impossibly large cup with Pepsi. I get a coffee, which only makes my heart pound more.

Once we’re in a booth, the tray of mashed potatoes and gravy and gargantuan Pepsi in front of her, she asks if I got everything I wanted. My voice comes out mechanical as I say yes and thank her for driving and coming with me. I have to get out of here. She smiles. “Of course, babe.”

We make it out of the store and back to my apartment without me dying. That night, I sit on the edge of my bed. The throw pillow and decorative bowl are still in the massive blue IKEA bag on the floor of my apartment.

The pulsing is still there, mixed with darkness and heaviness. At the time, I couldn’t have recognized the pattern: anxiety and panic rev up the mind, and depression is a way to subdue it in an attempt to restore homeostasis.

All I can think is that my new psychiatrist is wrong and those other therapists and psychologists and psychiatrists and GPs must have been right. There’s no hope. There’s no healing from mental illness.

The room becomes cloudy—not like a room. The overhead light haloes. I rub my palms together, but they seem like someone else’s hands.

Parents whose children have considered or attempted suicide or ended their lives ask me about suicidality. We think of it as feeling too much of what’s there, but for me, there was too much of what wasn’t there: not feeling, not seeing a future, not being able to imagine a moment beyond this one. Beneath the not feeling, the not seeing, the not being able to imagine a future, there’s a terrifying ache. It’s lurking and monotonous and seems impossible to escape. There’s only my mind telling me it will never end. My doctors and the internet and everyone know that I am mentally ill.

That night, almost on cue, the stringent narrowing starts. It’s as if I’m in a tube, the circumference of one end getting smaller. There’s barely a pinpoint of light. My body and maybe a square foot on every side is my whole reality. All the books I’ve ever read—including my favorites, the ones I escape into, novels like The Brothers Karamazov and Beloved and The Great Gatsby and Invisible Man—don’t exist. The films and TV shows and plays—none of it. No sun to warm my face. No memory of the six-mile walk I took yesterday in the bitter cold, the wind tightening my cheeks. The brick wall outside my window doesn’t exist. Not even the IKEA bag. My family doesn’t exist. No one exists. Not even me. Just the not and the ache.

Then the pinpoint of light expands. I imagine the sunny face of my therapist from the partial hospitalization program and remember the safety plan we set up. With the thought Call Elizabeth, my reality widens. I get my cellphone. It’s heavy in my hand.

There’s fear and love in my sister’s voice. Most of all, it’s commanding. She runs me through the safety plan. I trip as I walk the short distance from my bed to the kitchen counter to get the translucent orange bottle of Klonopin.

I tell her I don’t want to take it.

“Take it,” she says.

I swallow the little yellow pill.

“Now, the worksheet.”

I pull out a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) worksheet that’s more of a distraction than a savior. It bides time until the Klonopin knocks me out, ostensibly—if I sleep through the night—buying me another day.

Dazedly, I put the phone on speaker, get a pen, sit at the kitchen counter, and try to fill out the CBT Thought Record. My pen moves over the paper. My eyelids droop.

“How are you doing?” my sister asks, her voice a disembodied presence coming from my cellphone. I’d forgotten she was there.

She asks if I want her to wait until I’m asleep.

I get up, leave the worksheet, and take my phone with me to the bed. I lie down. “No,” I say. My eyes droop. We hang up.

Drifting in and out of sleep, it seems those other doctors must be right. My life will always be like this, won’t it?

It won’t, but I don’t know that. Without our safety plan in place—a very concrete, step-by-step plan of what to do when I felt suicidal (get your cellphone; tap Elizabeth’s number; wait for her to answer; if she doesn’t, keep calling until she does no matter how long it takes)—I might not have found out. That safety plan worked because it was specific, not Call if you need to or I want you to let me know if you feel this way again. And it didn’t necessarily involve the emergency room—where many people don’t want to go when in crisis—or a psychiatrist or therapist—who can sometimes feel like authority figures.

There were other options in terms of support, but I didn’t know about them. I could have called the suicide hotline, which at the time was 1-800-273-8255 and is now 988. (Note: If the crisis counselor deems a person a danger to oneself or others, the counselor will call 911—which may or may not be a relief depending on the situation.) I could have called a warmline, which, despite the name, are crisis hotlines manned by peer support specialists (people who’ve recovered from mental illness and addiction) trained to listen. And listen some more. And understand because they’ve been there too. Recovery respite centers—staffed solely by peer support specialists—offer a place where people can go when they’re in crisis.

*

The next morning, I wake groggy. A gauziness shrouds my one-room apartment. From the back of my mind comes a promise: You’re going to heal.

*

A few weeks later, I knock on the door of my mother’s apartment. It seems presumptuous to use my key. We say hello and hug awkwardly. She still feels fragile. All I want is for her to be better, for both of us to be better.

Her most defining feature is her eyes. They always seem to be moist with compassion yet attentive to whatever she’s reading or whoever is speaking. The exhaustion in them, which was so pronounced when I moved out two months ago, has faded but isn’t entirely gone.

The apartment smells of her. I hang my coat in the closet, where all my coats used to hang. It looks barren.

By the time I moved out, my departure was long overdue. No matter how much those of us with mental illness might need social support, it’s unfair to ask one person to provide it. She spent five years hearing me talk about my diagnoses and medications and symptoms, accompanying me to the emergency room, and being on suicide watch. It’s not that I didn’t help her during the years I lived in her spare room, but it was nothing compared to what she did for me.

The families have it the hardest.

We sit in the living room. As she speaks, her voice shakes. As always, she looks put-together and dignified but fragile. While I was breaking down, I broke something in her.

On Sundays, she says, she goes to church, something she never did before. “It calms me.”

With each tremor in her voice, I want to tell her how sorry I am for the strain I put on her, but that will mean talking about my illness, and she’s said she doesn’t want to talk about it.

I want to tell her about my plan to recover from mental illness—a process my psychiatrist, Dr. R, put in motion. I want to tell her about that night a few weeks ago, how that suicidal episode was different, how I knew either I was going to heal or end my life, and I decided to heal.

It’s not that we recover from mental illness simply by deciding to or that mental and emotional suffering is a choice. We don’t just “get over” psychosis or depression or anxiety or mania. Recovery isn’t a question of will; at the same time, it can’t happen if we don’t move toward it.

I want to tell her all of this, but that would mean talking about my illness, too.

She says, “I need to be more positive. It just can’t be so negative all the time.”

My mother dabs her nose with a balled-up tissue. It will take a long time for the exhaustion in her eyes to fade completely.

*

I never thought talking about my psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms was being negative; my diagnoses were my life—they were me. For twenty-five years and through six different diagnoses, my world was filtered through them.

It seemed to me I was just “talking through” my diagnoses and issues. Venting. Isn’t venting a good thing?

Turns out no. Research shows that it doesn’t even make the venter feel better; it can make things worse. Venting alone stokes the flames of complaint and negativity, as does ruminating about the past. As Ethan Kross, a psychologist and researcher at the University of Michigan, explains that solutions and relief arise from conversations that offer support and perspective. (This is what a good therapist often offers but not in my case.) The goal isn’t just to spew but to talk to someone who will help you step back and see the big picture.

Even without venting, it’s hard not to be negative. Doing so doesn’t necessarily entail positivity and certainly not toxic positivity—that unsettling, social-media-esque obsession with perfect happiness. Positivity doesn’t even come into it; it’s enough to limit our negative thoughts and perceptions.

*

My father and I sit at our usual table in Starbucks. He blows on his ginger tea. I sip from a latte.

His face is round, his cheeks a little jowly. At seventy-eight, he’s in good shape and sharp. His yellow baseball hat reads Cape Cod. His head is slightly large. Or maybe that’s just how I see it because although brain size and head shape aren’t indicators of intelligence, he’s the smartest person I’ve ever met. The facts he knows (e.g., the mating habits of the Patagonian toothfish) and the depths with which he can analyze historical and current events astound me.

He takes a hesitant sip of his tea.

My family is the only reason I’m alive. After my mother couldn’t be on suicide watch anymore, my sister took over. At the time, my sister and I weren’t even close. The years I’d isolated myself didn’t exactly lead to strong relationships. Yet she took it upon herself to be responsible for my life, an act of heroism that many family members and friends undertake every day without the appreciation they deserve. My father and stepmother helped pay for my care, which is something so many others don’t have.

My thoughts race. Nothing has caused them to do so—other than the caffeine. Racing thoughts are my default mode. For years, I’ve listened to audiobooks to try to drown them out. My mind is on repeat, a stream of self-criticism and worry.

Maybe it’s the caffeine. No one has ever asked if I drink caffeine. Just as no one questioned my drinking may years ago, no one has questioned whether someone with anxiety, depression, and mania—just maybe—shouldn’t drink a substance that’s been found to trigger a stress response, heighten sensitivity, interfere with emotional regulation, create a feedback loop, exacerbate mania, disrupt sleep, increase irritability and agitation, and cause a crash after the initial stimulant high.

I want to tell him I’m trying to recover too, but I don’t know what to say. It would have been a lot easier to explain it to them—and to myself—if Dr. R had said the words mental health recovery. A quick Google search might have told me that recovery centers on three basic principles: improving health, living a self-directed life, and striving to reach our full potential. These may sound like self-help platitudes, but they’re revolutionary to someone who’s only seen themselves as limited, broken, and hopeless.

There are two types of recovery: clinical and personal. Clinical recovery was once the standard, but it’s tricky. It demands the absence of symptoms. The problem is that the “symptoms” of mental disorders are part of the human condition. Anxiety, depression, mania, rumination, obsessions, compulsions, even psychosis are ways we respond to the world. We’ll never be rid of them entirely.

Which is why the standard today is personal recovery. The reduction of symptoms often occurs, but it’s not the goal. Medication is negotiable. It’s about having agency in our treatment and treatment goals, focusing on our strengths rather than what’s wrong with us and our lives, addressing past traumas, developing resilience, designing a life we can and want to have, and functioning well in that life.

The ambient sounds of Sarah Vaughn and frothing milk drift around us. It’s so tempting to say that I’m going to heal and make it all up to him. The door to the café opens, and a man enters, bringing frigid air.

Thanks so much for reading. To support my work, purchase Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins), the prequel to Cured. Both a memoir and a work of investigative journalism, it explores the ways we pathologize human experiences and ask, Is a psychiatric diagnosis a lifeline or a self-fulfilling prophecy?

You can also purchase a copy to donate to your local library or bookstore.

So well expressed. Suicidality is very much the ‘I just want this to stop’ feeling of nothingness. We want to be “better” but can no longer see this possibility.

It’s a loop our brains can get into that makes no sense when observed from far away. Ending the pain sadly removes our ability to heal. It’s a permanent solution to a temporary problem.

Concrete step by step plans are essential to all of us who reach a place where we are not thinking clearly. I want to hug Dr R. For showing you the pathway out of the woods.

It’s not easy, but it’s there.

You’ve walked this, Dear Sarah, and are a light glowing with the possibility of health for any who are in those horrid loops.

The key is to not believe everything we think. And to ask, what if I’m wrong? Then go thru the plan back to clearer thinking. Not easy, but possible.

I hope you always continue to share your story Sarah. It has already and will continue to save many lives.

a powerful essay. thank you.