On Fasting and Being Fed in the 1990s

My boyfriend Chris went out to our backyard vegetable garden and returned with two armfuls of freshly picked yellow squash. “They’re going to go bad,” he said with a smile and set to work in the kitchen.

The apartment we shared was perfect: a two-bedroom in a two-flat in a not-quite-gentrified neighborhood in Chicago. No one lived upstairs. It was like having our own little house. The wood floors were beat up, and the shabby windows drafted frigid air in the winters, but it had a big kitchen, a dining room, and what seemed to us like a huge backyard.

Our lives revolved around food-related areas: the kitchen, where Chris cooked; the dining room, where we had dinners with friends; and the garden.

It was his idea to grow vegetables. The garden bordered an abandoned lot on one side and an alley on the other. Only a barbwire fence protected the garden from the cars that sped past, kicking up gravel and dirt and trash. We were so proud of it.

In part, it was a response to the limited options for groceries. The local grocery store sold aisles upon aisles of canned food; ten-pound portions of frozen chuck roast; and wilting iceberg lettuce that was often out of stock.

We answered with plentiful harvests of zucchini, thyme, cilantro, and basil. Too much basil and so many tomatoes that we ate balsamic-tomato-basil salads for days in a row. Chicago had its first Whole Foods but compared to our homegrown peppers, theirs looked almost artificial in the glare of the store’s fluorescent lights.

That day, while Chris cooked, I took a bath. Our deep claw-foot tub wasn’t perfect. Scratches flecked its porcelain finish. One of the lion’s feet had broken off and been replaced by an iron stub and wood chips to level it. But the baths it gave enveloped and warmed me.

I wasn’t cold anymore. It had taken almost a decade, but I’d stopped starving myself. My freshman year in college, I fell into that strange limbo of eating just enough junk food to keep me bloated and not exactly thin—not eating all day and then giving into cravings for salty chips and sugary cookies. I’d throw in a sandwich or a salad to make it look like a meal.

Then I changed my major from honors English to Women’s Studies. I wrote essays on the male gaze and protested violence against women in Take Back the Night marches. My brain teemed with misogyny and internalized sexism and gender performativity. I learned how the patriarchy and big business and advertising and the media make women believe they were put on this earth to buy itchy lingerie and “trap” men into marriage.

I shaved my head—my long, light brown hair that reached the middle of my back became stubble. During the late shifts I worked at the campus deli, the drunk frat boys who’d once come in and hit on me (always in a creepy, taunting way) now seemed not to notice me. I was, in my unfemininity, invisible to them—and it was a relief.

Reading Joan Brumberg’s Fasting Girls sealed it. Brumberg wrote about women who retreated from society and denied themselves food as acts of defiance and assertions of their rights. During the Middle Ages, women like Catherine of Siena, Margery Kempe, and Julian of Norwich voluntarily emaciated themselves, their hunger making them so weak they hallucinated that God and/or Jesus visited them. The public saw them as mystics or saints, many going to them to be blessed, which undermined and angered the priesthood. After the Reformation, “miraculous maids” put their starvation on display to earn a living at a time when women had no economic rights. People paid to see them. It was the same in Victorian England, when “fasting girls” became a sensation in the press. Brumberg stressed the difference between voluntary fasting for a purpose and anorexia.

The book changed how I saw what I’d been doing. Those women were radical; I was senseless.

It also helped that the eating disorders unit and the therapists I’d seen were far away. No one was telling me I had an eating disorder. No longer defined by my -ia, no longer thinking in the appositive (Sarah, the anorexic), I stopped believing I was one.

While in the bath, I left the door open so I could hear Chris chop onions and click the burners on the stove and run the water in the kitchen sink. Our cat Cappy came in and mer-owed and rubbed against the tub and walked out. I didn’t ask what Chris was making out of all that squash. I’d eat what was given.

His relationship with food was one of devotion. When he cooked, each cube of bouillon, every clove of garlic, deserved respect. He ate healthy meals, usually stopped when he was full, and didn’t manipulate or fear food the way I had. On our days off, he’d cook all afternoon, making big batches of potato leek or white bean and fennel soup. Soup was the staple of our diet, mainly because it was cheap.

I finished my bath and dressed and sat on the couch to read. Our life together was simple. We had no internet. The TV stayed in the closet and was only brought out to watch the occasional show. We worked nights in the service industry—he as a bartender, I as a server. During the day and on our nights off, he wrote songs and performed with an avant-garde theater company on the South Side and I wrote strange, ethereal short stories.

In our social circles, without social media, we didn’t hunger for money and fame. It was the 1990s. Being “indie” was still possible, not watered down by the flatness of the internet. To Chris, the pinnacle of success was to be signed to the indie record label Thrill Jockey—which produced bands like The Sea and Cake and Tortoise.

I thought of writing, not getting published, and knew nothing about MFA programs and agents. My short stories were dreamy and plotless. We just wanted the next day to be as good as the one before.

There was a sense of plenty. Rent was affordable. Our furniture and clothes were almost all secondhand. We didn’t buy stuff. Most of our money went to CDs and books, and under-ten-dollars-bottles-of-wine and groceries, and food and catnip for Cappy.

Chris called me to the kitchen. On the table sat two steaming bowls of pureed yellow squash soup. It didn’t matter that it was warm out. We sat kitty-corner to each other.

Seven years older than I was, he was genuine and cool and talented and funny. My family loved him—my mother, my father, my stepmother, my sister, my brother-in-law—and his love for me was palpable. I’d never had anyone give of themselves the way Chris did. Early in our relationship, after finishing a solo hiking trip of a section of the Appalachian Trail, he drove his VW Bus all night to be with me as soon as he could.

He lifted his spoon and blew on his soup to cool it. I put my hand on his free hand and gently squeezed. He lowered his spoon to the bowl and wove the fingers of his other hand through mine.

“Thank you,” I said, my eyes tearing up.

He tilted his head, clearly surprised by the emotion squash soup had evoked in me. “You’re welcome.”

I raised our joined hands to my lips and kissed the back of his hand.

*

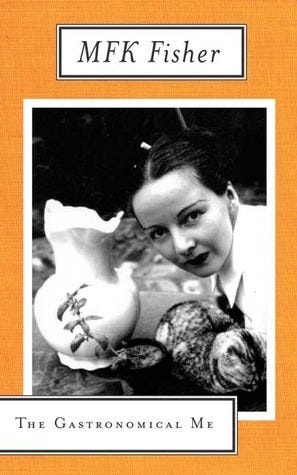

One afternoon on my way to work, I stopped at the used bookstore in our neighborhood. M.F.K. Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me stood on the shelf, facing out.

On the cover was a black-and-white photograph of Fisher wearing dark lipstick with her hair swept back in a bun, a chopstick holding it in place (exactly how I wore my hair). Fisher stared at the camera—bold, ready.

I’d never heard of her and didn’t know that she defined the American tradition of food writing as a mix of memoir, how-to guide, and adventure story. The book was a chronicle of her life as a woman with an unapologetically voracious appetite.

Standing there, I read the forward. She wrote that food is one of our three basic needs, along with security and love. The three were “so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others.”

Her adoration of food was methodical and nostalgic. I flipped through the book, stopping to read her description of eating an oyster in all its slick, briny distinctiveness; her reflection on dining practices in ancient Egypt and the love of yogurt and honey among the ancient Greeks; and her remembrance of how she kept the “wolf” of hunger at bay amid rations and food shortages during World War II.

That night at work, I sat with my coworkers at the bar folding napkins for the night’s service. Half of them were artists or aspiring actors who waited tables so they could pay their rent. Napkins folded, we polished the glasses and silverware and sampled the night’s special: skate wing in a beurre blanc sauce. My favorite: rich, buttery, the fish flaky but moist. No flicker of panic passed through me as it melted onto my tongue.

The restaurant was “cool.” With no street sign to indicate the entrance, you had to be in the know, which translated into annoyed and sometimes irate suburban patrons arriving late for their reservations.

There, food wasn’t just eaten, it was studied. The chef had taught me the nuances among filet mignon, Chateaubriand steak, and beef Wellington. I learned the difference between a broth and consommé, crudités and charcuterie, a tart and a galette.

When service started, I stood by the kitchen window waiting for someone to be sat in my section and talked with one of the line cooks about movies. Their shifts started in the early afternoon and, after their standing in front of a hot stove for six or eight or ten hours, ended whenever they’d broken down the kitchen for the night. And all for a fraction of what we made working a fraction of the time. Service, for them, was pressured and dangerous, given the sharpness of the knives and the extreme heat of the pans.

The cook I was talking to hitched up the sleeve of his chef’s coat. Burn marks striped his forearms. Food, I thought. He’d done that for the love of food.

*

THE NEW YORK TIMES: “Bristling with wit, warmth, and spiky intelligence,” a “fiery manifesto of a memoir.”

AN APPLE BOOKS PICK OF THE MONTH: “We were wowed by her talent for bolstering personal stories with takeaways backed up with careful research.”

Both a riveting memoir and a masterful work of investigative journalism, Pathological is a cautionary tale of what can happen when a young person over-identifies with a psychiatric diagnosis and continues to do so into adulthood.

A diagnosis can be a lifeline, but former advisory editor at The Paris Review and award-winning writer Sarah Fay used hers to limit herself and self-stigmatize without knowing the flaws and fallibility in our current diagnostic classifications.

Fay digs up her own life at the root to provide readers with the essential information needed to navigate a dangerous mental health system devoted to diagnoses—at all costs. Powerful, mesmerizing, and unputdownable, Pathological sits alongside other brave and inspiring classics that explore a more intelligent, forgiving, and nuanced approach to human suffering.

Pathological is a call for a new conversation about mental health diagnosis, one based on rigorous transparency and patient empowerment.

KIRKUS STARRED REVIEW: “Sharply personal and impeccably detailed, the book is bound to raise questions in the minds of readers diagnosed with any number of disorders.”

PARADE MAGAZINE 16 BEST MENTAL HEALTH MEMOIRS: “Using her 25-year journey through six misdiagnoses as a foundation, Fay takes a hard look at the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and raises some important and thought-provoking questions about its dominant role in mental health diagnostics.”

“Masterfully written, distinctively researched, deeply humane . . . Genius.” —ANTHONY SWOFFORD, international bestselling author of Jarhead

“This book is a triumph of the spirit and the flesh.” —ELIZA GRISWOLD, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Amity and Prosperity

Sarah, I felt warm as I read this excerpt from your book. So many layers here, so much nuance. What I connected with most was:

Living in a world pre-Internet and the joy and possibility of creating without the pressure of platforms,

Examining my relationship with food and how it has changed through the decades,

Appreciating the power of a moment, like a bath or a shared meal with someone I love.

Thank you for that gift today.

I am consuming your chapters with such intensity and pleasure. Thank you. PS. Recently subscribed to Substack Writers at Work - thank you for all the wonderful resources there as well. Regards from Cyprus.