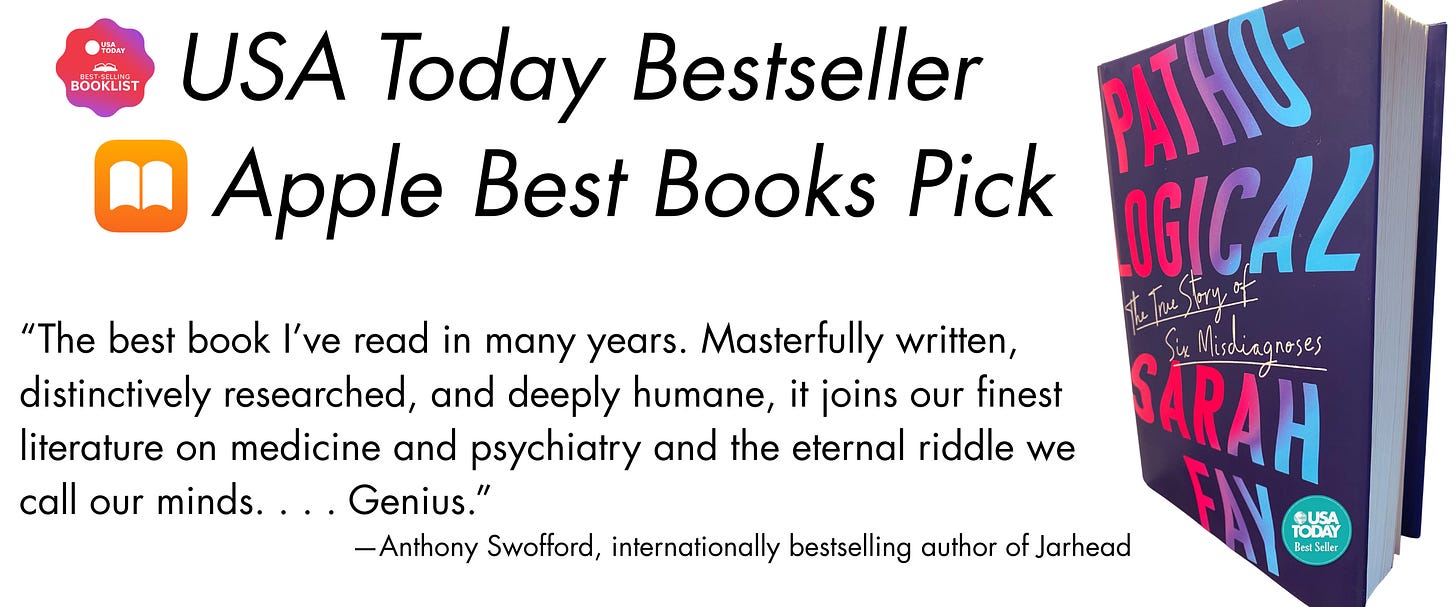

The best way to support my work is to purchase a copy of my national bestselling memoir Pathological, hailed by The New York Times as “a fiery manifesto of a memoir.” Pathological traces how we’ve come to believe that ordinary emotions are mental disorders and the twenty-five years I spent in the mental health system believing that psychiatric diagnoses are valid and reliable, which they’re not.

I.

My father stares pensively at his phone. We’re at our usual table in Starbucks. A water for me, ginger tea for him. I showed him how to download an app. He’s trying to do it. (He and my stepmother only recently agreed to get a cellphone.) He taps the screen and bites his lower lip.

My love for him encompasses me.

I still haven’t talked to my family about the fact that I’ve healed from serious mental illness. They were told I could only manage my symptoms. Healing actually feels like a betrayal. Will they think I faked it all those years? Will they think I’m lying about my recovery?

This morning, I sat at my desk and wrote the feelings and sensations that wreck me at worst or trouble me at best:

● Hollowness

● Vibration in my chest for no reason

● Pit in my stomach

● Insomnia

● Hypochondria

● Dislocation, feeling like I’m not in my body

● Panic attacks

● Needing to move

● Inability to stop moving

● Pessimism/negative thinking

● Hopelessness

● Inability to see the good

● Irritability

● Mood swings

● Negative self-talk

● Weighing myself

Before, these would have been symptoms; now, they just are.

He taps his phone, his forehead pinching in concentration.

To the sound of the barista calling out a double-skinny-iced something, the gravity of what I’ve done hits me: I’ve actually healed from mental illness—serious mental illness.

He looks up, defeated. “I can’t do this. Apple must only hire young people who hate their grandparents.”

I take the phone from him, feeling the smile on my face. We laugh together, not loudly but in a way we haven’t done in a very long time.

II.

I’m at my mother’s apartment. My sister’s sheepadoodle Augie follows her as she walks from the kitchen to the living room. A Kleenex dangles from my mother’s pants pocket. Augie eyes it greedily.

This has become a pattern. My mother takes care of Augie when my sister, brother-in-law, niece, and nephew go on vacation. It’s more stressful than fun. My mother loves Augie but being a dog sitter is a job best suited to, well, a dog sitter. Plus, Augie pooped on her rug. My mother worries she’ll do it again and won’t leave her alone in the apartment. So they’re together twenty-four, seven.

I come over every day to give my mother a break, taking Augie for a long walk to run with the dogs in the park—anything to tire Augie out so she’ll sleep, and my mother can read her books on Ancient Egypt and archeology.

Augie comes when I call her, trotting away from trailing after my mother in the hope of treats. I ask my mother what else she needs and what I can do.

“This is great. Just take her.”

Augie sits, her mouth moving in anticipation of a treat. She takes it from my hand as I clip her leash to her collar. “We’ll be back.” Augie gets another treat in the elevator and another once we’re outside and she pees.

My recovery feels almost complete: health, home, purpose, community. I live in a different brain. I have a home. My memoir, Pathological, will educate people about psychiatric diagnoses and save them from making the same mistakes I did. I have my family.

We walk—or rather Augie walks me. The air is crisp. Snow blankets the sidewalk.

How will I know when my recovery is complete? It’s been slippery and strange. What’s the you’ve-recovered benchmark? Do I need to have been happy for a year straight? Anxiety-proof and depression-free for a decade? Two years clean like in addiction circles? Five years without a trace of mental illness as with some cases of cancer?

III.

A few months before my memoir Pathological comes out, my father calls mid-morning on Sunday. I answer and ask how he is.

“Well, not very good.” His voice has the strain of someone who’s more confused than in acute pain. He tells me that he hurt his back. He fell but doesn’t remember falling. All he knows is that he fell and hit his head because there’s a wound on his forehead.

My father doesn’t have pain—or doesn’t talk about it; he complains only of arthritis in his hands. Even then, he minimizes it, saying it’s not that bad.

“I’m not going to be able to meet for lunch.”

His voice is so apologetic it makes me tear up. Then a pit forms in my stomach, the guilt for the way I treated him—and everyone—during the twenty-five years I struggled with serious mental illness.

Now that I’ve recovered, I look back on a lot of my life with regret, the feeling that I lost a quarter of it to psychiatry, the media, and so many clinicians perpetuating the myth that psychiatric conditions are biological, caused by a “chemical imbalance,” and lifelong. If only I’d known that none of these is true, I might have gotten well sooner. I might not have pushed my father away. I might not have become so hopeless I couldn’t live independently and was suicidal. That Sunday, I haven’t worked through the regret and grief that makes mental health recovery so hard.

I ask if he needs anything and I’ll miss seeing him. My stepmother is with him, so I don’t worry too much about him going through this alone. I tell him I love him.

“I love you too, hon.”

My chest surges with love, and the pit of regret hardens.

*

Hours later, he texts me. He’s in the ER. Immediate Care sent him there because his condition warranted more serious treatment. They’re going to keep him overnight for observation.

My sister calls. He actually fell yesterday. He’d been in the basement. Suddenly, he woke to find himself on the stairs, having fainted on his way back upstairs. He didn’t notice the gash on his forehead until a woman at the desk of his health club told him he was bleeding. Then, that Sunday morning, his back started to hurt.

The doctors diagnose him with bradycardia. His heart beats too slowly. A slow heart rate is typically a sign of good health. It’s the goal of exercise, meditation, and good sleep hygiene. But bradycardia is life-threatening. Not enough oxygen-rich blood pumps through the body. Undiagnosed, it can lead to cardiac arrest and death.

My father will have surgery the following day. The pacemaker will send electrical signals to his heart to make it beat faster. It’s a routine procedure. Minimal risks include infection, blood clots, and maybe a collapsed lung, but there are always risks.

That night, he texts. He says he doesn’t like being in the hospital. The next line practically breaks me: It’s lonely. I call and tell him I love him. He says he loves me too, his voice brittle and weak.

My father’s surgery goes well. He says he feels fine, except he’s hungry from not having eaten all day. I google visiting hours, which are almost over, and ask if he wants me to bring him a sandwich. He says the nurses are going to bring him something. He’ll be discharged by this evening.

The next day, I visit him and my stepmother. He answers the door. His cheeks are sunken, his skin wan. He looks very, very tired. As we walk inside, he’s unsteady on his feet. When we sit, he has to ease himself onto the chair.

He points to the part of his back that’s most painful and tells me that the doctors don’t know what he did to injure it. The cut on his forehead is already starting to scab. He shows me the scrape on his elbow. He’s never looked so fragile.

Something rises up in me, a pleasant vibration in my chest. Gratitude. I’m sure of it. I’m grateful he’s okay, so I can have more time with him.

Eventually, I start listening to a gratitude meditation on my walk each morning that asks me to think of three moments from my past that maybe I wasn’t grateful for then but could be now. Moments, not things. Scenes. Experiences. It takes a while—a year or so—but the regret I feel for the years I spent living with mental illness starts to fade.

A few months later, after my book has come out, my father leaves a message while I’m teaching a class on Zoom. I listen to the message after we finish.

He says he’s reading my book. “I love you,” he says. “I just want you to know I’m here.”

That same pleasant vibration fills my chest. It fills me to the point that my eyes brim with tears. Gratitude. It’s too late to call, but I text how much I love him and how grateful I am that he’s my father.

IV.

At our annual appointment, Dr. R asks how I’m doing. I went from weekly visits to monthly to bi-monthly to every few months, then every six months. I’ve since graduated to once a year.

I’m not sure what to say: I’m okay. Teaching is going well. I love my apartment. My family’s all healthy. I got a cat. Oh, and I totally healed from mental illness without telling you. And I wrote a book exposing the flaws in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness (DSM), psychiatry’s bible, and psychiatric diagnoses, and you’re in it. How are you?

Instead, I tell him I’m doing really well.

He bobs his head the encouraging way he does. “Good. Good.”

Gingerly, I tell him about getting an agent and selling the book. Even more gingerly, I explain that it’s about my years in the mental health system. More gingerly still, I mention my research on the DSM. “But I’m not anti-psychiatry. Not at all.”

He bobs his head knowingly. “Oh, yeah. The DSM? It’s just a mess. I tell my residents at the hospital, Don’t even go there. Stay in the real world. It’s a guide. Stay with your patient. I’m a biologist. I believe in science, but that’s not science.”

We talk for some time. I ask him questions about his experience with it and how he uses it.

“Well, it’s easy for me,” he says. “I don’t take insurance, so I don’t need to tell my patients they have the worst disorder so I can get reimbursed.”

His response to my book and honesty about the DSM fill me with trust—again.

He says, “Every medical resident should read your book, so they know what it’s like to be on the other end of the DSM.”

I want to tell him about my recovery. Instead, I stare out the window and become increasingly self-conscious. How am I “presenting”? How do I seem to him? What diagnosis do I embody? Would someone who’s recovered from mental illness stare out the window? Maybe she would. Maybe she just did.

We sit without speaking. How can I prove I’ve recovered? I don’t have any data marking how well I’m “managing” my symptoms. Anxiety is still an abiding part of my existence. Sometimes, it’s debilitating. Whirling dervishes of depression and darkness take hold. The sodden pit still comes. There’s no avoiding them.

Emotions and thoughts aren’t easy to manage. I wish there were an “atlas” of emotions, but it’s taken learning my bodily sensations and understanding which thoughts cause those sensations, and even then, I’m often puzzled because emotions don’t simply arise due to external events. There’s affect and mood, the ways that physical health and equilibrium—hunger, tiredness, blood sugar level, level of caffeine and other stimulants, etc.—create emotional responses. Our evolutionarily driven thoughts trigger them too.

As evidence of my recovery, could I present the way my self-talk isn’t cruel anymore? What about how strong I feel because I paved my path to recovery? Or how I wake each morning with a sense of purpose because I know my book will someday help improve the mental health system by giving patients the information they need about diagnoses? Or how when I’m at home, I still occasionally stop mid-kitchen or mid-living room or out on the balcony, amazed that I live in such a beautiful apartment with a view?

Could I use as proof my lunches with my father and phone calls with my mother and visits with my sister and brother-in-law every Saturday at 4 pm to walk Augie? What about how incredible it felt to hear my nephew introduce me as his aunt and realize, Yes, I’m an aunt, not a diagnosis?

Could I describe my love for my cat Sweets, who is so set in his ways? At night I lie in bed, and he lies ten feet away on the floor. It’s a kind of cuddling. The closets and under the bed are his territory. When he stretches out, exposes his belly, and gives me a haughty look, the likeness to Henry VIII (not the Buddha) is unmistakable.

Would my gratitude practice count toward my recovery?

What if I told Dr. R I’ve recovered, and he disagreed?

Maybe he already knows.

V.

On Sunday, my father and I have lunch. We sit on stools at a bar table at the Japanese restaurant where we eat each week. The waiter, who knows our order by heart, comes to the table to confirm. (Routine: I eat the same thing almost every day, and it’s rubbed off on my father—at least during our lunches.) It’s early, and the restaurant is practically empty.

It’s time to tell him—someone—I’ve recovered, but I don’t know what to say.

My father tells me a story he’s told before. I love to hear him tell it. He and my mother lived in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in the 1960s. My father helped translate the government documents written in French into English. (He’s fluent in French.) One night, my father and mother had some of his Ethiopian colleagues over for dinner. My father is a masterful cook and dinner-party host. He served doro wot (spicy Ethiopian curry) as well as French pate and cured meats. He also put out a jar of Dijon mustard.

“Just regular Dijon,” he says. “Nothing special.” He smiles and tells of how his colleagues had no reaction to the spicy curry. “But the Dijon made their mouths burn. I hadn’t thought about it. The spice in mustard seed affects a different part of the mouth.”

It’s a story he delights in, likely because the years he and my mother lived in Ethiopia were some of their fondest together. Travel brought and kept them together for twenty years.

Our food arrives. My father opens his chopsticks. I do the same.

“Dad.” I hesitate. “I think I’m well. I mean, I think I’m cured. Not sick anymore—at all.”

He nods, certain. “I know.” He smiles. “I know.”

Support my work by buying a copy of Pathological. If you’ve already purchased a copy, thank you! You can gift a copy to a friend, your local library, or your favorite used bookstore.

Oh wow, Sarah. This is so intimate and powerful. I’m also so grateful for your recovery. Also: I love your dad.

Beautiful, Sarah. You had me fully inside you, feeling each chapter, right through to your dad's "I know."