Grief Work and Giving a Book New Life

People warned me it would happen.

I’m on the recumbent bike pedaling, just peddling in my building’s exercise room. My workday is ahead of me. It will proceed methodically: workout, shower, eat, see clients, write, walk, work, work. No grief work scheduled—grief work a term I hadn’t even heard of until my mother was dying.

But as I pedal and stare out the window at the surrounding buildings that seem to be cracking against the cold and the withered, dry hydrangea bush bracing itself in the wind, the song on my headphones sparks a memory: I’m walking down the street, ironically outside where I went to school from kindergarten to third grade, to visit my mother at the assisted living facility. It’s warm. Summer. Dusk.

I’ll get to see her—bright-eyed despite dementia, her curly dark hair dyed so she looks sixty, not eighty-two—let her take my arm and guide her from the dining room back to her room, sit with her, help her shower and find her pajamas, tasks I sometimes felt were a chore.

The song shouldn’t spark that memory. It’s Gracie Abrams’s “I Love You. I’m Sorry,” which isn’t at all about the love of a child and parent.

But grief doesn’t care. I’m crying, tears streaming—a clichéd portrait of grief. There’s a person on the treadmill, so I try to control the heaving.

It’s the moment so many have come to: Oh, wait, this is permanent. My mother is never coming back. Her death isn’t some temporary glitch.

The thought of others going through this maybe having encountered this moment is such a comfort. The timing seems right: the burial and shiva/memorial are over, the condolences have thinned.

I could get up and go into the bathroom and really sob, but that’s a terrifying idea inside a sobbing that seems will never stop. Scary sobbing beneath still-as-possible shoulders.

I could remind myself that she’s “better off,” having dodged the twelve-years-or-more-of-living-with-Alzheimer’s bullet.

I could stop the song.

Instead, I play it again, thinking of my grief counselor who’s teaching me to “dose” my grief. I don’t want to miss out on this dose.1

*

Grief looks a lot like depression and for someone who lived with serious mental illness for twenty-five years, it’s a slippery slope.

Grief and depression have similar textures but opposite pulls. Grief is a penetrating hollowness that makes you want to connect with almost anyone. Humans—any creatures—are a lifeline: my best friend from high school who’s come back into my life, my cats, dogs on the street, my family (oh, to sit in front of their TV watching football games I don’t understand the rules of), you through my writing, my clients, my subscribers to Substack Writers at Work, my doorman Michael (whose generosity is unparalleled), my dentist (true). They don’t fill the hollowness but act as a connector within it.

Depression is a penetrating hollowness that makes you want to isolate. To not pet the cat, not text, not call, not speak. All so as not to feel. The hollowness just expands.

I worry about falling back into depression, but I also know I won’t. It “would have been okay” in the I’m-not-ashamed-of-mental-illness way, but it’s not what I want for myself.

*

They say the only people who want to hear about grief are the grieving and those who’ve grieved. The fact that you’re reading this says so much about the grief work you’ve done in private—or your ability to open your mind to a topic we too often avoid.

You had to have done your grief work in relative private because “grief work” was never on my radar before. Doing this alone would break me. Thinking of you and imagining you consoled consoles me.

*

People keep saying I’m doing so well. They can’t believe I’m back on Substack and teaching. It’s because it’s not coming from a place of avoiding my mother’s death and the loss. It could, easily, but it’s not.

My mother loved four things about me in particular. (Think of someone you’ve lost and what they loved about you.) Yes, she loved my humor, my kindness, my energy. She also loved that I was a writer and a teacher, that I’d recovered from serious mental illness and wanted to help others do the same through my writing, and that I’d built a successful business.

So that’s what I’m doing, immersing myself in what she loved. It’s busy-connection, the opposite of busy-avoidance.

Right before she died, when she wasn’t scared all the time because her dementia made everything new and threatening, she’d say, “Wow” a lot, as if the world was a wonder.

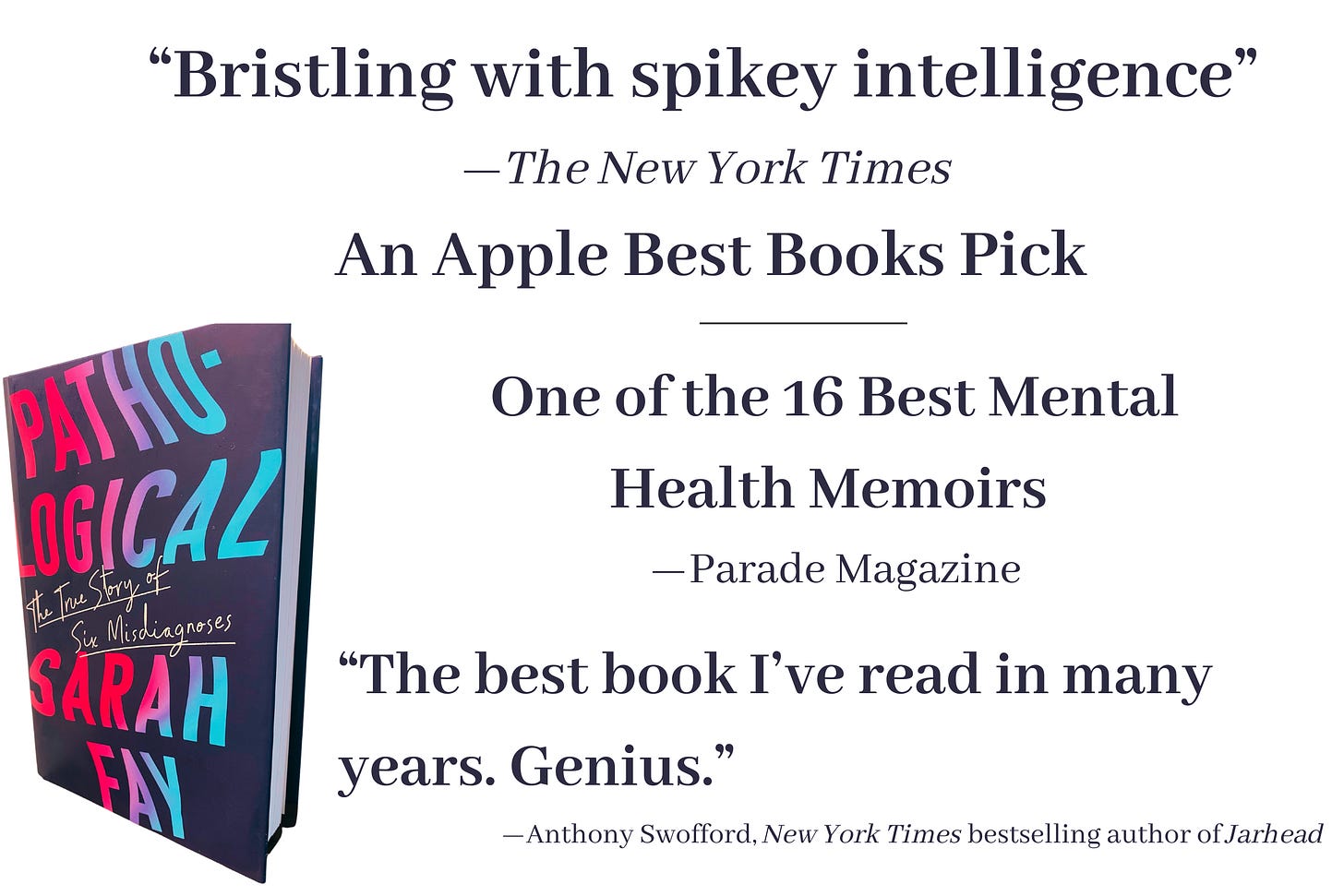

We sat in her room at the assisted living facility—I on her blue couch and she on her favorite chair, though she’d often forget it was her favorite. I told her I was working with a branding agency to relaunch my memoir Pathological because it didn’t sell as many copies as we wanted and so much of what I feared about the public—especially young people—using psychiatric diagnoses against themselves has come to pass.

She looked at me and said with absolute love, “Wow, that’s so great.”

My mom had a hard time reading my memoir Pathological because she’d lived it. At first, she apologized and said she’d never be able to read it. I understood. She’d lived with me through the worst of it—had saved me—and my breakdown had almost broken her. Reliving it in my book would be too hard, too upsetting.

But then she did. And bought six copies, three of which remained on her bookshelf and now sit on mine.

Relaunching a book isn’t part of an author’s career. Publishing revolves around only what’s “new.” The latest release. We publish a book and have about three months to get on a bestseller list, which, unless the zeitgeist is with you or you have a lot of insiders pulling strings, is nearly impossible. Then our publishing house stops publicizing our book. No matter how brilliant or potentially life-changing for people, our beloved book ends up on what’s called the backlist. My agent once bemoaned the bookshelf in her office filled with her clients unjustifiably backlisted books.

Rebirthing Pathological and getting it into the hands of people who need it will be challenging. The goal is to reach as many parents and physicians as possible, so they can be empowered by learning who the truth about psychiatric diagnoses and can better help their children and patients receive the best care, i.e., one that leads to recovery, not maintenance.

I’m determined to appear on fifty podcasts and radio and television programs and speak at thirty conferences and businesses and universities.

*

The sloppy tears stream down my face and my shoulders heave too much as my playlist moves on to Taylor Swift’s “Down Bad,” which also isn’t at all about the love for or loss of a parent. (You knew one of my playlists would include T-Swift.) I laugh when she sings, “Down bad crying at the gym.”

I’ve never thought much about the dead or the afterlife, but my mother will be with me. And that means doses of grief and feeling down bad and crying at the gym.

*

I need your help:

If you are or know someone who is any of these, please email or DM me with their contact information so I can pitch you/them:

Podcast or radio program host or producer

Talk show host or producer

Journalist who cover health and wellness or mental health

Anyone who runs a physician residency program or hospital grand rounds

Any business that might want someone to speak during Mental Health Awareness Month (May)

Anyone who runs a conference of any kind

Email me or DM me:

@sarahfayauthor

mssarahfay1516 [at] gmail.com

And if you haven’t purchased Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins) and want to receive or help your loved ones receive the best mental health care possible, you can buy or gift it to someone here:

Let’s change the world—or at least our mental health system—for the better.

If you have ideas or suggestions for my book relaunch or want to share your grief work, please share in the comments.

I’d never heard of grief counselors before. If Dina Bell-Laroche of The Grieving Place hadn’t been there, I would be a disaster right now. I also have to mention the amazing Barri Grant who’s invited me to her grief group.

Sarah Fay, I am literaly sitting on my recumbent bike pedaling off to foreign lands in my mind where a few things still count for something - and I'm listening to the Pink Floyd album Wish You Were Here. "Shine on you crazy diamond - remember when you were young and you shined like the sun."

Thank you for sharing this poignant piece. My dear mother just had her second knee replacement a few days back ~ 82. Bless her as she is good spirits. I'm hoping and not hoping that she is and is not doing it on my account. I rather like your thoughts on the similarities and differences betweet grief and depression.

I am sorry for your loss, of course, and yet it is nice to hear that you are immersing yourself in what both you and your mother love, yourself and moving forward as best you have learned to do reaching for what you want.

Love this and you. More thoughts on grief: My view is that I must be in touch with this pain and understand that grief has its own time table. This is hard stuff. _The Year of Magical Thinking_ by Didion. _Grief is the Thing With Feathers_ by Max Porter. _Lincoln in the Bardo_ by George Saunders. And might I share for others, as you've read this, my take on the death of my son, truly to share: https://marytabor.substack.com/p/lifeboat ~Love Mary